| Home Contents Contact |

|

|

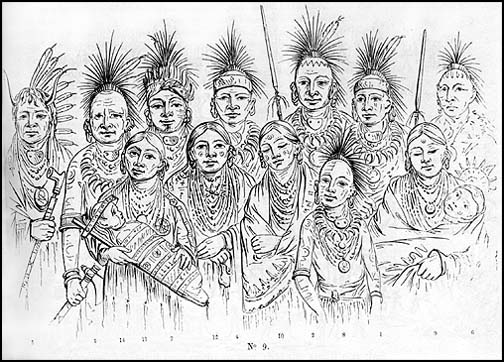

The original complement of fourteen Ioways who came to Scotland with George Catlin in 1845. The child in the cradle towards the left is Corsair, who died at Dundee. Holding him is his mother, O-kee-wee-me, who later died in Paris. The man standing at the extreme right is No-ho-mun-ya, known in English as Roman Nose, who died at Liverpool and was buried in a grave whose location has been forgotten.

Let it not be falsely imagined that Buffalo Bill Cody was the only or even the first showman to exhibit parties of Native Americans in Great Britain for mass popular entertainment.In 1839, Pennsylvanian lawyer turned adventurer, writer and artist George Catlin came to England. Taking up a three-year lease on the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, London, he exhibited his Indian Gallery consisting of nearly six hundred paintings of Native American subjects, together with the vast collection of native artefacts and costumes which he had amassed over several years of travels among the western tribes. Catlin moved to Liverpool in 1843 and shortly thereafter undertook a tour of the provinces.

Catlinís Scottish venues in 1843 were:

A logical extension to Catlinís lectures was the employment of local actors to model his costumes and demonstrate the use of his weapons. This feature of his appearances was enormously enhanced when in 1844 he was joined by a party of Ojibbeways, with whom he undertook tours of England and the European continent. These Indians were granted an audience with the young Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, by whom they were presented with a large quantity of tartan plaid.

6th, 7th, 11th - 14th April Edinburgh Waterloo Rooms 18th - 21st April Glasgow City Hall 22nd, 24th April Paisley Exchange Rooms 25th - 28th April Greenock The Theatre

The Ojibbeways departed when Mr Rankin, who had been responsible for bringing them to England, decided to terminate his arrangement with Catlin. Rankin continued for a time to exhibit them independently and they appeared in Edinburgh at the Waterloo Rooms, Regent Bridge, in July 1844.

These Ojibbeways were succeeded by a party of fourteen Ioways, and in January 1845 Catlinís itinerary brought them over the border into Scotland. The towns and cities visited this time around were Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee, Perth, Edinburgh again, and finally Greenock, from whence the party sailed to Dublin.

Catlinís own account is curiously lacking in detail and it is an oddity of his style that he provides very few dates in the course of his narrative. A precise time-frame can however be reconstructed on the basis of contemporary newspaper reports and advertisements. Notice in particular that whereas Catlinís own narrative places Glasgow between the second visit to Edinburgh and Greenock, which would have been perfectly logical, extraneous evidence clearly indicates that Glasgow was in fact the first of the 1845 Scottish venues.

The towns and cities in which Catlin and the Ioways appeared in 1845 were:

23rd - 25th, 27th - 29th, 31st January - 1st February Glasgow City Hall 3rd, 5th, 6th February Edinburgh Music Hall 7th (cancelled), 8th, 10th February Dundee Thistle Hall 11th - 12th February Perth City Hall 15th, 17th, 18th, 19th February Edinburgh Waterloo Rooms 20th - 21st February Greenock The Theatre The Ioway performers enacted tableaux vivants in addition to a variety of songs and dances.

In Glasgow, the medicine man Se-non-ti-yah (Blistered Feet) conceived a fascination with Glasgow Universityís Hunterian Museum, then located in the High Street, while the other Indians of the party were drawn to what Catlin termed a Ďbeautiful cemeteryí1. This is surely a reference to the Necropolis, which had been opened twelve years previously.

The scenes of desperate poverty encountered in Glasgow surpassed anything the Ioways had witnessed in any of the towns and cities previously visited and they adopted the practice of throwing pennies to the ragged apparitions they passed in the course of their daily horse-drawn omnibus drives. Word quickly got out and gangs of beggars took to hanging around their door in the hope of meeting them as they came out.

The Ioways bore the constant proselytising attentions of missionaries from the usual bewildering array of Christian denominations with fortitude but there were occasions when their patience wore thin. In Glasgow, a visit from a pair of clergymen was received without enthusiasm and the remarks of the war chief, Neu-mon-ya (Walking Rain), if correctly recorded by Catlin, represent a searing indictment of the Indianís impressions of conditions witnessed in Scotlandís largest city:

My friends - I am willing to talk with you if it can do any good to the hundreds and thousands of poor and hungry people that we see in your streets every day when we ride out. We see hundreds of little children with their feet in the snow, and we pity them, for we know they are hungry, and we give them money every time we pass by. In four days we have given twenty dollars to hungry children - we give our money only to children. We are told that the fathers of these children are in the houses where they sell fire-water, and are drunk, and in their words they every moment abuse and insult the Great Spirit. You talk about sending black-coats among the Indians: now we have no such poor children among us; we have no such drunkards, or people who abuse the Great Spirit. Indians dare not do so. They pray to the Great Spirit, and he is kind to them. Now we think it would be better for your teachers all to stay at home, and go to work right here in your own streets, where all your good work is wanted. This is my advice. I would rather not say any more.2 Catlin esteemed Edinburgh Ďthe most beautiful city in the kingdom, if not one of the most beautiful in the worldí3 and there, on 4th February 1845, the Ioways took time out for sight-seeing. The capital attractions visited included Salisbury Crags, Arthurís Seat, Holyrood House and the Castle, where they duly inspected the crown of Robert the Bruce.

Shon-ta-yi-ga (Little Wolf) came to Scotland in 1845 with George Catlin. His son died in Dundee, and his wife in Paris.

A baby boy aged eight months and named Corsair (after the steamer on which he was born, while sailing on the Ohio river) died on 8th February 1845, shortly after the Ioways arrived at Dundee on board the steamer from Edinburgh. After appropriate tribal ceremonials, the child was sent for burial at Westgate Hill Cemetery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, under the direction of the Society of Friends or Quakers, a religious organisation which had come to enjoy the confidence and esteem of the Ioways during the course of their British sojourn. The cemetery, which then stood on the outskirts of the city, has since been allowed to fall into a state of sad disrepair. If the grave was ever marked, the inscription would appear to have been worn away with time but its location is preserved with some precision in the records of Newcastle City Council. The funeral was conducted on 12th February 1845.

Westgate Hill Cemetery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne

In Perth, Catlin and party received an invitation from Sir William Drummond Stewart to visit him at Murthly Castle, which Catlin, with his characteristic inattention to detail, refers to as ĎMerthylí Castle. Catlinís busy schedule, however, compelled him regretfully to decline.

The Indian number was further reduced when one of the men died in Liverpool. Corsairís mother subsequently succumbed to tuberculosis in Paris, and was buried at Montmartre. The eleven survivors now lost heart and decided to go home.

Twelve of the Ioways with Mr G. H. C. Melody, their conductor, and Jeffrey Doraway, their interpreter

The second party of Ojibbeways which quickly succeeded the departed Ioways suffered similar reverses and three of their number, the only full bloods in the party, died of smallpox. A horrified Catlin - who had recently been bereft of his wife and was shortly to lose his youngest child, a little boy of three-and-a-half-years, also named George - urged his Indian charges to return home immediately. They unwisely disregarded this advice, and continued to tour on their own account. Further deaths would follow.

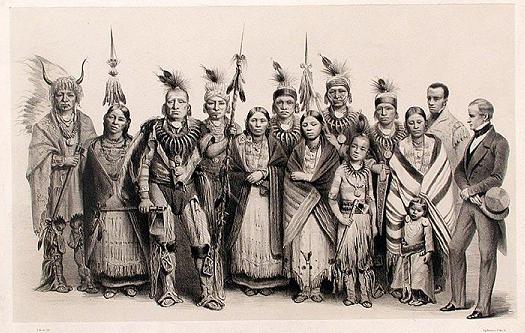

The head man of the party, whose native name is variously rendered as Mangwadaus or Maun-gua-daus (second from left in above group photo), was otherwise known as George Henry. He gave a description of his adventures, published in Boston in 1848, entitled An Account of the Chippewa Indians, who have been Travelling among the Whites, in the United States, England, Ireland, Scotland, France and Belgium; with very interesting Incidents in Relation to the General Characteristics of the English, Irish, Scotch, French, and Americans, with Regard to their Hospitality, Peculiarities, Etc. He lost a son in Edinburgh on 4th April, followed by a daughter and further son in Glasgow on 7th and 12th May 1847. These deaths are recorded in the Society of Friendsí Digest of Births, Marriages and Burials (held at New Register House, Edinburgh), which records that all three were interred in Edinburgh, although the precise location is not entered. However, the small Quaker cemetery on the Pleasance, in use from 1820 until 1876, is most probably indicated.

Dumbarton Rock from Langbank, 29th July 2010

A few days more, the incidents of which I need not name, finished our visit to the city of Glasgow; and an hour or more by the railway, along the banks of the beautiful Clyde, and passing Dumbarton Castle, landed us in the snug little town of Greenock, from which we were to take steamer to Dublin.4 Footnotes:

1 George Catlin, Adventures Of The Ojibbeway And Ioway Indians in England, France, and Belgium: Being Notes Of Eight Years Travels And Residence in Europe, in two volumes, Vol. II, published by the author, 1852, Kessinger reprint, p. 173

2 Ibid, p. 176

3 Ibid, p. 163

4 Ibid, p. 177. Note once again that Catlinís recollection of the sequence of events is wrong. The visit to Greenock with the Ioways directly followed the second Edinburgh sojourn of the 1845 tour. Glasgow had been the first venue on the tour.