| Home Contents Contact |

|

|

Peter was fortunate, however, for Wilson turned out to be the most considerate of masters and, having no children of his own, treated Peter as his adopted son. When Peter was seventeen, Wilson died and left him a respectable sum of money, his horse, saddle and all his wearing apparel. For the next seven years, he made his way as an itinerant labourer, at the end of which time he married the daughter of a substantial planter. He settled down to married life on a tract of land of two hundred acres’ extent on the edge of the Pennsylvanian frontier, of which all but thirty acres had yet to be cleared.

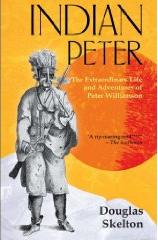

The ‘captivity narrative’ represents the most perplexing form of frontier literature; it is difficult to classify examples of this genre as sober first-hand accounts or as propaganda directed against the native population and those sympathetic towards them. One of the most lurid of these recounts the intensely eventful career of Scotsman Peter Williamson (1730-99), which began in Aberdeenshire and ended in Edinburgh, with a lengthy and traumatic period of exile in North America in between times. Quite an extensive range of published articles exists on the subject, not least of which was a section of Chapter 2 in The Diamond’s Ace but Douglas Skelton is to be congratulated on having since succeeded in coaxing an entire book out of Williamson’s life story. By his own admission, Skelton is a storyteller, not a historian but I suspect that he is being unduly modest and that his account will stand unsurpassed for some time yet. Williamson was born in Hirnlay, Aboyne Parish. Some years later he was sent to live with an aunt in the flourishing seaport of Aberdeen. There, while playing one day with his companions in the vicinity of the harbour, he was accosted by two ruffians who seized him; after a lengthy period of detention he was put on board a ship bound for the American colonies. There was a thriving trade operating in Aberdeen, a nefarious enterprise which for a long time avoided suppression and even operated quite openly through the direct complicity of several magistrates and leading citizens. Far-fetched as it might seem, this was people-trafficking, eighteenth century style. Individuals could quite competently bind themselves to a period of indentured service but the absence of the necessary element of consent and the lack of legal capacity of many of the youthful victims of this odious practice were mere technicalities to be conveniently overlooked.

After a voyage packed with terrifying incident, young Peter was finally brought to Philadelphia where, for £16, his articles of indenture were assigned to one Hugh Wilson, himself a native of Perth, or to give that city the archaic name by which it was known to Williamson, St Johnstown.

On the night of 2nd October 1754 - while his wife was away visiting relatives – a party of Indians allied to the French, during the opening salvos of the as yet undeclared French and Indian War, attacked Peter’s home and took him prisoner. One extremely curious omission is that in his account Peter does not identify the tribe by name. Different commentators have proposed the Cherokee and the Iroquois but linguistic and other clues strongly implicate the Delaware (the view quite correctly taken by Skelton). Bound to a tree, Williamson watched in abject horror as his assailants looted his home and then burned it, destroying all that could not be taken away. Loading their plunder onto his back, they forced him to carry it for them.

Soon after his capture, Williamson was tortured but passed the ordeal and his life was spared. His sturdy build, which was apparently what had recommended him to the kidnappers of Aberdeen in the first place, was precisely what saved him now. The Indians, who had yet to acquire mastery of the horse, intended to exploit his physical strength and resilience by using him as a beast of burden.

In the course of this further period of involuntary servitude Williamson routinely witnessed atrocities perpetrated upon his fellow settlers. Three Ulster Scots were taken prisoner and, after an unsuccessful attempt to escape, were horrifically tortured to death in his sight. We must never forget that before there was the ‘Wild West’, there was the even wilder east.

The elderly, when no longer capable of supporting themselves, were summoned before a tribunal of the chiefs and condemned to death. Sentence was executed upon old men by young boys and in the case of old women, by girls. The child selected for the task bludgeoned his or her venerable victim with a tomahawk, thus becoming inured to death and violence from an early age. The corpse was then interred, with grave goods, in an upright position.

The snows came, forcing a temporary cessation to the depredations, as tracks left in the snow made it too easy for pursuers to read their trail. Williamson was held in the native settlement of Alamingo, where he built himself a wigwam and subsisted on Indian corn together with a little meat which his captors periodically allowed him. During this period, he had ample opportunity to observe the Indians’ material culture at first hand and makes a number of remarkable claims about the things he witnessed.

Describing a further aspect of the demonically harsh penal code which he found in place, Williamson narrates:

They are very strict in punishing offenders, especially such as commit crimes against any of the royal families. They never hang any; but those sentenced to death are generally bound to a stake, and a great fire being made round them, but not so near as to burn them immediately; for they sometimes remain roasting in the middle of the flames for two or three days before they are dead.1 The snows cleared and the raiders went out once again; Peter’s packhorse status was resumed. One day, as the Indians slept soundly, exhausted after a hunting party, he was presented with the opportunity to flee. Vividly recalling the infernal punishments meted out to the three Ulstermen, Peter knew the risk he was taking but take it he did. The Indians awoke to find him gone and after a terrifying and lengthy chase through the forests, he narrowly succeeded in evading the hellhounds on his trail, eventually reaching the homestead of an old neighbour, who scarcely recognised him in his pitiable condition. It was the beginning of January 1755 and his hideous ordeal had lasted more or less precisely three months.

After a brief spell of recuperation, Peter borrowed a suit of clothes and a horse from his host and set out for the house of his father-in-law, arriving on 4th January. From exquisite relief he was quickly plunged into sorrow as he learned that his wife had died about two months before. Thereafter, he was primarily motivated to see himself ‘revenged on the hellish authors of my ruin’.2

He next enlisted in one of the colonial militias and participated in an expedition to rescue the daughter of one Joseph Long Esq., the sole survivor of an assault which had been carried out against her father’s plantation. A graphic and hideous description of the manner in which the young lady’s brother was tortured to death is included in Peter’s account of the episode.

Williamson was then stationed for a time at Fort Oswego, where he was afforded an opportunity to study a considerable range of Indian nations at first hand. Once again, he offers a number of quite extraordinary observations upon the Indian mores.

The religious life of the Iroquois, he informs us, was dominated by a mortal dread of evil spirits. His most shocking claim is that for the first seven days of each new moon, these Indians would make their oblations to the evil spirits and that during this time they would select one of their number to suffer the most excruciating torments that they were able to devise, in the belief that through this blood sacrifice, the wrath of the demons would be appeased. To what extent this assertion may be taken as responsible anthropology or is better interpreted as lurid sensationalism is a matter on which others will no doubt feel compelled to take a view but on which I feel unqualified to comment.

Following the fall of Oswego, Peter was taken prisoner by the French and repatriated, arriving at Plymouth on 6th November 1756. He had sustained an injury to his hand, leaving two fingers permanently disabled and was discharged from the British army with the award of the princely sum of six shillings (30p in today’s money).

He then proceeded to walk home all the way to Aberdeenshire. He ran out of funds at York but was able to secure the publication of a manuscript in which he recounted his adventures. He made his way as a strolling player, dressing in his Indian costume and performing a war dance to attract the crowds, who were then invited to buy his book.

Finally returning to Aberdeen, he rediscovered his unfortunate penchant for being taken prisoner for what was mercifully the final time, as the merchants and magistrates took exception to the early part of his account in which he told of the shameful manner in which he had been kidnapped and forced into what was slavery in all but name.

Fined 10/-, forced to retract and banished furth of Aberdeen, Peter had no sooner established himself in Edinburgh than he advertised himself, e.g. in the Edinburgh Evening Courant of 7th October 1758. Parties of at least six persons were invited to call upon him at his lodgings where, upon buying a copy of his book for one shilling, they would entitle themselves to witness his costumed war dance without further charge. On the evidence of The Grand Magazine, for June 1759, it would seem that Peter continued to tour his one-man Wild West show for a while longer:

Mr Peter Williamson… being come to London, where he exhibits himself in Indian dress, displaying and explaining their method of fighting… With his usual resourcefulness, he set up a coffee house within the precincts of Edinburgh’s Court of Session. He was persuaded by one of his lawyer clients to raise actions against the Procurator Fiscal and magistrates of Aberdeen. In the first of these, he was awarded relief for the recent wrongful prosecution against him and in the second he received substantial damages for the original kidnapping which had been the genesis of all his subsequent calamities.

Peter earned renewed fame in Scotland’s eastern metropolis by means of his annual publication of the city’s first postal directory and his introduction of a ‘penny post’ service for Edinburgh and its suburbs. In a city never in danger of running short of eccentrics and notables, he soon acquired the status of something of a local character. The sign above his tavern door in Old Parliament Close styled him ‘Peter Williamson, Vintner from the Other World’ and a wooden carving of Williamson in Indian dress stood by the entrance. On occasion, he was known to exhibit himself in his Indian costume to the delight and astonishment of his customers. Further publications and re-issues of his adventures followed under a variety of titles. Such was the renown of ‘Indian Peter’s coffee-room’ that it was even named-checked in The Rising of the Session, a poem by Robert Fergusson, who would almost certainly be esteemed today as Scotland’s national poet, had he not met with the singular misfortune of being outshone by his immortal contemporary, Robert Burns.

Peter Williamson died in 1799 and at his own direction was buried in an unmarked grave in Edinburgh’s Calton Hill cemetery, clad in the American Indian accoutrements which he had carefully preserved and brought home to Scotland with him.

It has been strongly suggested by a number of writers that Peter Williamson’s American adventures supplied the inspiration for the A Man Called Horse film trilogy but Skelton specifically denies this. However, Williamson’s account forms part of the overall Scottish literary heritage from which Robert Louis Stevenson must have drawn and the plight of David Balfour, the central character in Stevenson’s classic novel Kidnapped, bears at least superficial similarities to the early misadventures of the young Peter Williamson. It is even plausible that Williamson exerted a crucial influence upon J. Fenimore Cooper’s fictional work, The Last of the Mohicans.

Skelton exerts himself to place Williamson’s astonishing tale within its appropriate historical context. Indeed, at times, his book appears to consist of context and little else. However, Skelton’s skilful treatment of the French and Indian War provides an extremely useful introduction to the main outlines and inner dynamics of this pivotal and most American of conflicts. (Indian Peter – The Extraordinary Life and Adventures of Peter Williamson, Douglas Skelton, Mainstream Publishing, Edinburgh, 2005)

Footnotes:

1 Life and Curious Adventures of Peter Williamson, p. 30

2 Ibid, p. 38