| Home Contents Contact |

|

|

|

|

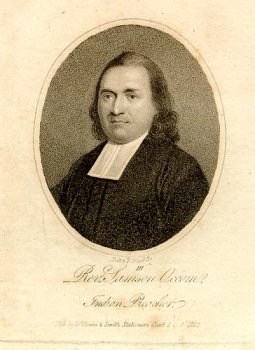

At the age of seventeen, Occom became a sincere convert to Christianity. He was appointed a missionary to the Montauk, marrying one of the female members of that tribe and eventually gaining the distinction of becoming the first Native American to be ordained a Presbyterian minister.

In Scottish Highlanders and Native Americans – Indigenous Education in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World1, Professor Margaret Connell Szasz scrutinises the parallel careers of her two highlighted ‘cultural intermediaries’, Samson Occom (1723-92) and Dugald Buchanan (1716-68), each of whom dedicated himself to the spreading of the Presbyterian gospel within the cultural parameters of his own respective tradition. Buchanan, a catechist and schoolmaster, was a native of the Highland portion of Perthshire, while Occom, reputedly a lineal descendent of the famous sachem Uncas, was a New England Mohegan. Occom’s prodigious intellectual depth and the breadth of the cultural divide bridged by him are evinced not only by his acquisition of a mastery of written and spoken English but also by his successful absorption of Latin and Greek, together with some Hebrew. In 1765, he was selected to travel to Great Britain on a mission to raise funds for Moor’s Indian Charity School - founded by Eleazar Wheelock at Lebanon, Connecticut, eleven years previously – in company with Nathaniel Whitaker. It is clear that Occom provided the ‘exotic’ element upon which the success of the venture depended, given that the perennial fascination of the people of England, Wales and Scotland with ‘Red Indians’ had already taken a firm hold.

There is an eerie parallel with the later British tours of Buffalo Bill Cody, in that the latter’s English venues in season 1887–88 are exhaustively documented, while almost nothing, until recent years, had been published on his equally eventful and even more successful forays into Scotland. A similar unaccountable pattern has manifested itself in respect of Occom. I am personally obliged to Professor Szasz for having conducted much-needed primary research into Occom’s time in Scotland in 1767, and it remains to be confessed that when I wrote my first book, The Diamond’s Ace – Scotland and the Native Americans, one of the stories which completely passed me by was that of the Mohegan Indian who became a Presbyterian minister and delivered sermons to congregations in Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Paisley and elsewhere in the northern kingdom, where he was evidently far better received than on any other leg of his tour. In Edinburgh, Occom preached at the Tolbooth Kirk. In Glasgow, Occom and Whitaker apparently lodged with Mr George Brown, a local merchant, on the Trongate.

Recalling the dictum famously and (almost certainly incorrectly) attributed to Black Elk, that he had signed up for Buffalo Bill’s season of 1887 - 88 ‘because I might learn some secret of the Wasichu that would help my people somehow’2, I would like to offer a perspective of my own, that Native Americans subscribed in great numbers to the mysteries of one or other of the various Christian denominations for essentially the same motives that later led them to enlist with Wild West shows. Both these routes appeared to hold out the prospect of a guaranteed entrée into the dominant civilisation.3

Buchanan and Occom’s respective Edinburgh sojourns overlapped by a couple of months – Buchanan was in town to supervise the printing of the Gaelic version of the New Testament - but Professor Szasz has been unable to resolve the crucial question of whether the two men ever actually met.

For all that Occom served his white masters well, he remains a tragic figure, a quintessential victim of racial perfidy. During his term of duty as missionary to the Montauk, he was remunerated with a salary which was much less than would have been payable to a white man in precisely the same position.

On his return from Great Britain, he was mortified to discover that his wife and children had almost perished through Wheelock’s wilful neglect. The culmination in a litany of betrayals came when the money which he had laboured so hard to raise on the other side of the ocean was not after all applied to its original purpose. Occom, in the face of a society which simultaneously commanded conformity while denying admittance, retreated far into the interior in what is now upstate New York to establish the ‘praying town’ of Brothertown on land granted by the Oneida, one of the six nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, in favour of the remnants of Algonquian tribes displaced from the east.

From this new centre of operations Occom maintained his commitment to the white man’s religion, while at the same time doing his utmost to keep his distance from the white man himself.

Full text of ‘Samson Occom and the Christian Indians of New England’Footnotes:

1 University of Oklahoma Press, 2007

2 Neidhart, Black Elk Speaks, p. 214

3 This line of reasoning becomes all the more pressing when one considers the following extract from The Object at Hand, an article about Kicking Bear, by David Ewing Duncan in the Smithsonian, September 1991:

I succeeded in contacting Mr Duncan via an e-mail link but he was unfortunately unable to recall his source for this story. It will be remembered that Kicking Bear was a ghost dance enthusiast who toured Great Britain and spent several months in Glasgow as a performer with Buffalo Bill in 1891-92. I would however call into question Mr Duncan’s assumption that Kicking Bear would have viewed his involvements as a ghost dancer and a Christian as mutually incompatible activities.

Soon after his Washington visit (i.e. in or shortly after 1896), he turned up in Montana as a Presbyterian missionary, preaching, among other things, the story of Jonah and the Whale. But by 1902 he had abandoned Christianity and was teaching new converts the ways of the Ghost Dance again.