| Home Contents Contact |

|

|

by Kim Twatt Printed and published by Herald Printshop,

27, Albert Street,

Kirkwall, Orkney KW15 1HLTel. (01856) 875039

e-mail orkney.herald

@btopenworld.comPrice: £6.00

+ £1.00 P&P

Hannah (Kingfisher) was William Twatt’s grand-daughter. She had always told her children they were descended from a Scottish man but no-one had really taken her seriously. She had told her children that some day someone would come from Scotland looking for their family. She had been told of my intended visit just before she died. In recent years genealogy has gone from strength to strength as a leisure pursuit. More and more people – myself included - are taking up the challenge of tracing their own family’s place in history. Frequently, this leads to the discovery of relatives in distant far flung places, who as often as not can fill in a lot of the blanks and add an entirely fresh perspective on shared ancestry. Particularly with the coming of the Internet and computer-based databases, this field of study has long since ceased to be the preserve of specialised academics.

I have had the good fortune to meet a lady with a family history project which most of us can only dream of. For Kim Twatt from Orkney kindly sent me a copy of her colourful and well illustrated little book, recounting her personal experiences of a remarkable success in tracing and befriending distant cousins among the Cree Indians of Sturgeon Lake First Nation Reserve in Saskatchewan, Canada.

Sturgeon Lake Reserve from the air

(Courtesy of Robert Foden)

The story began in 1999, when Kim, who organises walking tours of Kirkwall in Orkney, had an encounter with a Mr Hulme from Vancouver, who had come to carry out research into Orcadian forebears on behalf of several compatriots.

Mr Hulme expressed particular interest in a man named Magnus Twatt (1751 – 1801), who had entered the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1771. Coincidentally, Twatt was Kim’s maiden name, although these days she also goes by the name of Mrs Foden. Her investigations on Mr Hulme’s behalf promptly revealed that Magnus Twatt had indeed been related to her - a direct ancestor was Magnus’s uncle.

It remains a disquieting fact that Canada’s wealth was built on the sordid foundation of the fur trade, an activity which remains both economically significant and ethically indefensible in the 21st century. At the time of the European discovery of the Americas, the landmass was initially perceived as an inconvenient obstruction preventing westward access to the rich markets of the orient. A breed of hardy adventurers emerged to trade furs from the Indians for resale in Europe and as a pattern was set for the opening salvos in frontier history, several animal species were plunged towards extinction.

During the final years before the American War of Independence, when Magnus Twatt enlisted as a labourer in 1771, the Orcadian port of Stromness was the final port of call for ships in the service of the HBC making the outward voyage to North America. There they took on board supplies of food, water, and most importantly, labourers. Orkney men bore the reputation of being ‘dependable, hardy, obedient and adaptable’1, and made up about two thirds of the entire workforce.

Magnus Twatt prospered with the HBC, and only ever returned to Orkney for one extended visit between 1795 and 1797. During this sojourn he made a will, providing inter alia a bequest for the establishment of a school in Kirbister (the Twatt Mortification School, built and in use from 1804).

His employment as a fur trader in Canada’s wilderness interior, far in advance of the nearest European settlements, brought him into close contact with the native population, by whom he was apparently held in high regard. Like countless others in similar circumstances, he took a Cree wife, known as Margaret, who bore him two sons, and a daughter named Elizabeth (Betsy). Betsy later married Alexander Bremner, a farmer originally from Caithness, by whom she had twelve children. Alexander died at the Métis Red River settlement in 1842, and Betsy finally followed him to the grave in 1885.

Much detail about Magnus’s two boys, Mansack and Willock, followed from contact (via the Internet) with Paul Thistle of Canada, who had composed a paper entitled The Twatt Family, 1780 – 1840: Amerindian, Ethnic Category, or Ethnic Group Identity? Kim was quietly amused to discover that Mr Thistle had laboured long and hard to discover the ethnic origins of the forenames Mansack and Willock, and she was able to enlighten him that Mansack is the South Ronaldsay equivalent of Magnus, and that in the same dialect Willock equates to William.

Resorting once again to the Internet, Kim stumbled upon a fax number for the Sturgeon Lake First Nation band office. The name Sturgeon River had cropped up in the course of her researches, but beyond that, her faxed message bearing the vital question, ‘Has anyone ever heard of Magnus Twatt?’, was no more than a stab in the dark. As it later transpired, Sturgeon Lake Reserve lies hundreds of miles distant from Sturgeon Landing, where she mistakenly thought that her fax had been sent.

Quite fortuitously however, the response, which arrived in early 2001, was a wonderful surprise. She had found her lost relations.

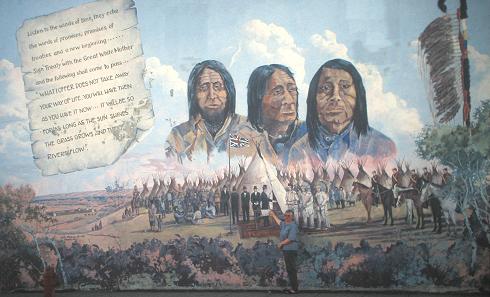

Until the 1940s, the Sturgeon Lake First Nation had been known as the William Twatt Cree Band, after its founder, Chief William Twatt, son of Mansack. William was one of the chiefs who in 1876 was obliged to sign Treaty Six, in terms of which more than 121,000 square miles were handed over in exchange for an allotment of one square mile for each family, in addition to annuities and other benefits.

A family holiday to Canada followed, in the course of which Kim was reunited with her Cree relatives. At a lunch given in honour of Kim, husband Robert and twelve year old son Alistair, Chief Earl Ermine presented her with a star blanket. They were also made honorary members of Sturgeon Lake First Nation, a tribute seldom and not lightly bestowed.

The first of the reciprocated visits came in the spring of 2002, when Professor Willie Ermine of the Saskatchewan Indian Federated College and his son Charles visited the islands. The Ermines constructed a sweat lodge at Minehow in Tankerness, using willow branches kindly donated from a garden in Orphir and stones from the beach at Inganess. Willie also contributed to the Iron Age Conference, held in Orkney that year.

The following August, the Fodens returned to Canada, this time taking with them an Orkney chair for the Sturgeon Lake council chamber, crafted by Colin Kirkness and paid for by donations from the people of Orkney.

Tara Daniels, Sturgeon Lake Cree, Orkney 2004

(Courtesy of Orkney Photographic)

Two years later, in 2004, a party of twenty-five Cree Indian dancers, singers, storytellers etc. provided the star attraction at the 14th Orkney International Science Festival. Their participation was made possible by funding from a number of public bodies, together with private donations from local people.

Willie Ermine gave an emotionally charged address, based on his experiences of industrial residential school, at a day of lectures entitled Airbrushed Out of History, and reduced his audience to a stunned silence.

At a sell-out performance by the dancers in the Pickaquoy Centre:

One elderly Orcadian, moved to tears, wiped his eyes and was heard to say: “Those drums, they really get inside you, don’t they?” (Orkney Today, Friday, September 10, 2004)

Wes Stevenson, Vice President of the First Nations University (‘Your kind do not make it here’, Wes had been told upon first entering University) invoked the image of ‘a trunk with two roots’ as representing the party’s dual origins.

Nor was the rapport with the Orcadians a purely theoretical one, for the visitors, conspicuous in bright red jackets, soon established themselves as familiar and popular figures relaxing in local cafés and passing the time of day with locals on the streets.

The Orkney telephone directory made for an unlikely but particular source of fascination for the Indians. It contained common instances of such surnames as Flett, Isbister, Drever, Harcus, Linklater, and Rendall. Even the Indians had previously assumed these, widespread in and ostensibly exclusive to their own community, to be First Nation names, and had been unaware of their true origins. Genealogist Alexander Dietz from Saskatoon, who was also in town, confessed that he had not realised the full extent of the connection.

A group of young dancers danced on the sand at Pierowall in Westray. They were astonished to find themselves stranded on a sandy island, never previously having experienced the tide.

Most of the dance troupe made a pilgrimage to the ruined cottage at Kirbister where Magnus Twatt had once lived. As Kim continues the story:

It was a moving visit. There Terry (Daniels) told me the reality and realisation that he was walking the same ground his ancestors had walked came to him as he had listened to a prayer being given in Cree in Orkney’s St Magnus Cathedral. He knew he belonged in these islands.

The visit to the ruined cottage at Kirbister

(Courtesy of Robert Foden)

The visitors also brought with them an invitation for the representatives of the people of Orkney to participate in the July 2005 Sturgeon Lake powwow.

Nine people made the journey, including the Fodens, Orkney’s Director of Education, and five others. On the Saturday morning, a pipe ceremony was held. Elder Bill Ermine prayed in Cree, but pronounced that he was praying for both of the communities which had joined together. He prayed that the bonds would grow stronger, and that each community would learn from the other.

There followed a visit to Asini Kanipawit, a circle of limestone boulders inspired by the previous year’s visit of the Indians to the Ring of Brodgar in Orkney. One lady had brought with her a bag of stones from Warbeth Beach, near Stromness. The Orcadians, whose visit it had been erected to commemorate, were asked to lay these stones around the circle. The final line of the accompanying inscription reads:

Asini Kanipawit is dedicated to our common ancestors.

The foregoing is no more than a rude synopsis of Kim’s marvellous little book, which I thoroughly recommend to anyone interested in learning the full story of this remarkable interaction between two cultures ostensibly distant and diverse, and yet closely connected by a common history and ties of blood.

The writing on the wall – Kim Foden at the Treaty Six mural, Duck Lake

(Courtesy of Robert Foden)

Footnotes:

1 p. 3