| Home Contents Contact |

|

|

(Photograph courtesy of Mrs Gertrude Fillmore)

As everyone knows, the American Indian’s troubles began with Christopher Columbus in 1492, according to what passes as conventional wisdom anyhow. In defiance of the orthodox view, an entire genre has arisen dedicated to championing the ‘veritable procession’ - in Niven Sinclair’s graphic phrase - of those who are variously asserted to have beaten Columbus to it. Included in the rollcall are the 11th century Prince Madoc of Wales and an Irish contender, St Brendan. These traditions of early Celtic incursions into North America are connected to claims of genetic and linguistic affinities with the Celts, first popularised by George Catlin in 1841, which are claimed to have been displayed by the Mandan tribe of North Dakota. Unfortunately, since the Mandans had been virtually eradicated by smallpox four years previously, it is hard to test this hypothesis in accordance with the full rigours of modern scientific method.

Then we have the Vikings of the Vinland Saga, who maintained a presence in Greenland from 985 AD onwards and had Scottish runners in their employ. A conscientious examination of the globe suffices to reveal two most salient facts. Firstly, the island systems of the North Atlantic provide a series of convenient staging posts. Secondly, the crossing is far shorter here than further south, over the route followed by Columbus for example, from southern Spain to the Bahamas. Clear archaeological evidence now indicates that colonies, later abandoned, were established by the Norsemen at various points along the eastern seaboard. What, in my view, truly stretches credulity to breaking point and beyond is the proposition that they made it across a cold and raging ocean to the forbidding shores of Greenland but were then unable to venture further.

Needless to say, Scotland has a candidate of its own, in the shape of Prince Henry St Clair, Earl of Orkney, reputed to have landed on Nova Scotia in 1398, almost a full century ahead of Columbus. His proponents also claim that he established himself as the white, bearded deity Glooscap of Micmac Indian tribal legend, who arrived upon a floating island. Glooscap was the friend and teacher of the MicMac; all their useful knowledge was imparted by him. Legends of this kind are remarkably prevalent throughout the Americas, the most noteworthy instance being the parallel tradition of Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec god whose predicted return paved the way for Cortez and his Conquistadores during the years 1519-21.

The tradition places Prince Henry at the intersection of several important historical strands. His ancestors were of Norman origin, those sea-going Norsemen who settled in the north of France and adopted the language and manners of their chosen homeland. The bearers of the St Clair (Holy Light) family name, acquired during this period, next crossed the English Channel around the time of William the Conqueror and settled in Scotland, where they rose to prominence and were granted extensive landed estates in various parts of the country, including Lothian and Caithness. Over time, ‘Saint Clair’ evolved - or degenerated - into the more familiar Scottish surname of ‘Sinclair’.

The Saint Clairs are also implicated with the Knights Templar, the enigmatic military and religious order whose origins lie in the Crusades. They came particularly to be associated with the Temple of Solomon and the elusive Holy Grail. After the order was brutally suppressed in 1307, by order of the Papacy, some survivors were warmly received in Scotland. It has been suggested that their involvement in the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 was the decisive element in the Scottish victory. Their esoteric doctrines thus laid the foundations for Freemasonry. By the act of receiving these ‘heretics’, Scotland distanced itself from Rome, providing a vital link in the chain of events which ultimately culminated in the Scottish Reformation. In the more immediate term, the Knights Templar provided the impetus for attempts to found a new Jerusalem beyond the western seas.

In addition to his Scottish estates, Henry held Orkney as a vassal of the Norwegian king and this is what entitled him to the title of ‘Prince’. This status, which involved him in a highly ambiguous position of joint allegiance to both the Scottish and Norwegian sovereigns, also entailed the obligation to impose royal authority upon the wild inhabitants of Shetland and the Faroes.

Documentary support for a voyage of discovery to North America by Prince Henry in the last years of the 14th century rests mostly upon the pseudo-historical Zeno Narratives, published in 1558, together with (far from convincing) attempts to identify him with one of the central characters, Zichmni.

Amongst the transatlantic physical evidence adduced is the ‘Westford Knight’ rock carving in Massachusetts, which has been interpreted as a memorial stone to a member of Clan Gunn who died there; also a petroglyph at Clark’s Point, Maine, depicting a cross and a sailing ship with a single sail and stern rudder, of a type in common use during the century preceding 1450. The Newport Tower, Rhode Island, conforms closely in the principles of its construction to the Templar and Scottish architecture of the period. The unit of measurement on which it is based is the Scottish ell. According to local Narragansset Indian tradition, this mysterious stone tower, for which conventional wisdom can provide no satisfactory explanation, was built long ago by ‘fire-haired men’ with green eyes.

Prince Henry is said to have returned to Orkney in 1400 and to have been slain in an armed engagement not long after. It is also conjectured that an intensification of hostilities with England prevented the relief of any colonists who may have been left behind.

Rosslyn Chapel

William, grandson of Prince Henry and third and final Saint Clair Earl of Orkney, founded Rosslyn Chapel, near Edinburgh, in 1446. This building is mysterious and a fascination to crypto-historians for a variety of reasons, not least for the central role which it plays in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. For present purposes, however, it is of interest for the stone carvings which it incorporates, of several plant species, amongst which are alleged representations of aloe cactus and Indian corn, both of which, under the conventional view, were unknown in Scotland at that time.

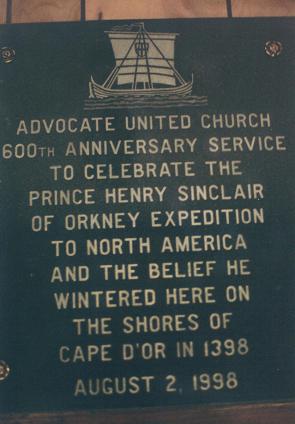

No one suggests that Prince Henry was in any sense the ‘discoverer’ of North America; essential components of the theory postulate that others had preceded him. The argument in favour is not without its limitations nor for that matter is it short of opponents but the fact remains that the purported voyage and North American adventures of Prince Henry St Clair are widely commemorated; celebrations were held at Guysborough and Advocate, Nova Scotia, and also at Westford, Massachusetts, in 1998, to mark the 600th anniversary of Prince Henry’s alleged arrival in 1398.

In addition to the granite tablet (supra) which graces the foyer of Advocate United Church, the memorial stone in the Mariners Memorial Park, dedicated on 10th October 1999, bears a plaque in celebration of a long and proud heritage and whose inscription acknowledges that the region is ‘claimed to have been visited in 1398, by Prince Henry Sinclair’.

(Photograph courtesy of Mrs Gertrude Fillmore)

The ‘Sinclair Symposium’, organised as part of the Orcadian Science Festival, was held from 5th to 7th September 1997 and was supported by an impressive range of local civic dignataries, writers and representatives of the Micmac tribe. The keynote address, presented by Niven Sinclair, bore the carefully-chosen title - Beyond any Shadow of Doubt.

Source: Andrew Sinclair, The Sword and the Grail, (London: Random House UK, 1993)Brian Smith’s scholarly rebuttals are duly noted.