| Home Links Contact |

| 1887-88 1891-92 1892 1902-03 1904 |

|

|

It is difficult to ascertain exactly what an Indian thinks, but it is beyond all question that those forming Colonel Cody’s troupe have had their ideas very much enlarged by their visit to England, and four of them at least have become so enamoured of English civilisation that they declined to put in an appearance when their companions left Manchester on Friday last, for four of the number did not answer to the roll call, and where they are now I do not know. They did not turn up as it was thought they might do at Portland, and the steamer sailed away without them.

- The Hull News, 12th May 1888

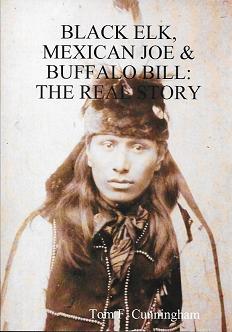

Black Elk, Mexican Joe & Buffalo Bill - The Real Story

by Tom F. Cunningham

Westerners Publications Ltd

First published Spring 2015

16,000+ words

43 pages

BookIn 1887, William F. ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody brought his Wild West show to England for the first time. One of the Indians with the show, a young Oglala Lakota named Hehaka Sapa (Black Elk), was one of six performers, including four Indians, who were left behind in Salford, Greater Manchester, shortly before the show set sail for the United States on 6th May 1888, at the season’s end. Stranded, Black Elk and his companions made their way to London where they joined up with Mexican Joe, a rival Wild West showman, with whom they toured in the hope of raising their passage home.

The extraordinary saga of Black Elk’s exile from exile and subsequent redemption was first published in 1932, in John G. Neihardt’s seminal work, Black Elk Speaks. The original interview transcripts were made available decades later, in the form of The Sixth Grandfather – Black Elk’s Teaching Given to John G. Neihardt, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie.

It is immediately apparent that Neihardt’s lyrical narrative is not supported by The Sixth Grandfather in crucial respects and yet it has long been uncritically accepted at face value.

A proper scrutiny of relevant primary sources such as contemporary newspaper coverage and passenger lists has finally been conducted, revealing Black Elk’s story of his brief career as a show Indian, originally recounted by him in his native tongue, as a departure from the form in which it was first presented on his behalf and re-told on numerous occasions by a succession of derivative authors during the intervening eighty-three years. Specifically, Mexican Joe’s ascertainable movements during this period differ significantly from what we have previously been led to imagine.

A number of questions necessarily arise:

- The other Indians whom Black Elk identifies as having been left behind with him in England – were they five or three in number? Who were they and what became of them?

- Who was the mysterious ‘English-talker’ who helped Black Elk and his friends to make their way in England? Was he really an Indian?

- Did Mexican Joe really tour Germany and Italy through 1888 and 1889 as Neihardt claims? Black Elk’s allusions to Naples, Pompeii and Vesuvius are plain enough but was he ever really there, or does an alternative explanation exist?

- Black Elk was in Paris with Mexican Joe during the summer of 1888. Neihardt tells us that the show returned in the spring of 1889 and that Black Elk, who had fallen ill, was nursed back to health there by a white girlfriend and her family. Was Black Elk’s girlfriend really a Parisian, or did she live somewhere much closer to home?

The overwhelming majority of the Indians who travelled abroad with Buffalo Bill returned home in a state of awe and, firmly convinced that continued resistance to the white men was futile, threw in their lot with the cause of ‘civilization’. Following his return to Pine Ridge, Black Elk became a ghost dancer and participated in the hostilities which briefly flickered in the wake of the infamous massacre at Wounded Knee. Why was Black Elk’s reaction so different from the others and do his experiences in England hold the key to a proper understanding?

Definitive answers to these and related issues are attempted in this innovative study. Those who, in common with the author, have for years been captivated by the story of Black Elk’s European misadventures should now prepare themselves for a few surprises.