| Home Links Contact |

| 1887-88 1891-92 1892 1902-03 1904 |

|

|

Chief Iron Tail - tipis and tenements

(Image Courtesy of Heritage Auctions)

Iron Tail (Sin’tè Màza), an Oglala Lakota, presents something of an enigma. Paradoxically, whilst his movements with the Wild West are very well documented and an extensive photographic record exists, very little is known about his earlier life. Despite his billing in the show, we can be certain that he was not a political figure of any significance. Insofar as he can be described as a historical character, he was a manufactured one. Scouring the indexes of the main texts on the Sioux Wars, one draws a blank time and again.Considerable caution has to be exercised with information found on the internet, for there is a common tendency to conflate Iron Tail with Iron Hail (known in his later years as Dewey Beard), which is quite certainly erroneous.

One of the precious few sources on his origins consists of an entry for a young man named Iron Tail (Sin-te-ma-za) in the Sitting Bull Surrender Census, taken at Standing Rock, dated 22nd September 1881. He was a member of a family belonging to a band led by Big Road and Low Dog. The head of the family was Little Hawk, aged 49; living with him were his wife, White Horse (Woman), 50; his mother, Pretty Otter Skin (Woman), 80; and his five sons, of whom Iron Tail, aged 24, was the eldest. It might therefore be inferred that Pretty Otter Skin was Iron Tail’s paternal grandmother. White Horse was probably his mother but given that polygamy was a common practice among the Lakota, we cannot be certain. His four brothers, or half-brothers, were Left Behind, 18; One Who Rides at Daybreak, 17; Bald Head, 10, and Running Amongst Them, 7. The first two are given in reverse order in terms of age but it is not immediately clear why this should be so.

The personal property associated with the household amounted to two horses and four dogs. Forty-three buffalo and no deer had been killed during the previous year.

The inclusion of Little Hawk and his family on this occasion almost certainly indicates that they had lately been in exile in Canada with Sitting Bull, who had taken refuge there between 1877 and 1881.

Little Hawk was evidently a man of some importance. Ephriam D. Dickson III indicates that:

Little Hawk (ca. 1836-1899), an uncle of Crazy Horse, surrendered at Fort Keogh on 14 June 1880 with 585 people, representing a number of different bands. He later settled in the Wakpamni District on Pine Ridge.1 Little Hawk had been entered as a member of the the ‘Crazy Horse Sioux’, in close proximity to Crazy Horse himself, on the occasion of the latter’s surrender on 6th May 1877, but there is no indication that his son was with him. Iron Tail is not mentioned in the Crazy Horse Surrender Ledger or in any of the associated agency records; his whereabouts at this time are therefore unknown.

Iron Tail’s place of birth is unknown; his age can only be estimated but the various official records associated with him tend to indicate that he was born in the early 1850s. The 1881 census record moves this back to c. 1857.

Richard Green2 bravely implements the oblique strategy of supplying at least some of the many missing details by inferring substantive information from the graphics depicted on a muslin shield belonging to and possibly made by him; thus concluding that Iron Tail may have been a member of the Oglala Elk Dreamer Society.

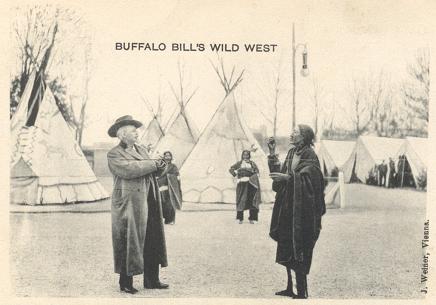

Buffalo Bill and Iron Tail in the tipi encampment, c. 1905

For close on two decades, Iron Tail was Buffalo Bill’s constant companion; visiting newspapermen often found the pair together in the Colonel’s tent. A film has been preserved of them conversing in sign language.

According to Dr Colin Taylor:

When Buffalo Bill formed his Wild West Show in 1883, he engaged a number of famous old Indians, among them Iron Tail who stayed and travelled with Buffalo Bill’s Shows through all their tours.3 This is extremely questionable. Despite having undertaken extensive research into the Indian performers, I have found no indication of Iron Tail’s involvement on the 1887-88 English season, 1891-92 tour of Germany, Belgium and Great Britain, 1892 London season, or 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

Of the few official Wild West rosters to have survived, Iron Tail is not listed in 1896.

His participation on the 1898 season is established by photographs taken by Gertrude Käsebier at her New York studio on 24th April. Michelle Delaney states that he and Short Man were leaders of the Indian Police in that year.4

In the 1900 Census, Iron Tail (Sinte Maza), 41, was listed as residing, apparently on Pine Ridge Reservation, together with his wife, Red Horn (He Luta), 44, and daughters Ellen, 9, and Katie, 7. In the next household listed were Philip Iron Tail, 21, and his wife, Annie, 19.

In the same year, Iron Tail was noticed as ‘Principal Chieftain’ at the head of ‘about forty-five full-blooded Sioux Indians of the tribes Brule and Ogallalla’5, alongside Chiefs Black Fox and Lone Bear.

His return in 1901 is indicated by an article, according to which his wife was hit on the head by a falling tent pole, on the night of 24th April as the couple sat in their tipi on the show grounds in Washingon D. C.6 Iron Tail’s close personal connection to Buffalo Bill beyond his employment in the Wild West show was highlighted when, on Tuesday, 12th November 1901, he and ‘Chief Bucking Horse’ participated in a parade and grand ball at Cody, Wyoming, welcoming the arrival, from Toluca, Montana, of the first Burlington train in town.

In the other surviving roster, Iron Tail is entered as one of five chiefs on the 1902 tour of North America.

I have found no record of him returning to the company for the English and Welsh season of 1902-03.

He was however very conspicuous as a leading attraction on the 1904 tour, in which he was present from beginning to end, arriving at Liverpool on board the Umbria on Sunday, 24th April 1904, and travelling literally the length and breadth of Great Britain before departing from the same port on board the Campania on Sunday, 22nd October.

The 1904 season got off to a most inauspicious start, with Iron Tail sustaining contusions to the chest and abrasions to the heel in a train crash at Maywood, Illinois, on Thursday, 7th April. It is noted that Philip Iron Tail, almost certainly the elder Iron Tail’s son, then in his early to mid twenties, was listed among the fatalities. It is a testimony to Iron Tail’s standing within the tribe that those who had escaped injury then gathered around him as he led them in a death song. This was the same accident which came close to claiming the life of Luther Standing Bear, effectively ending his career as a show Indian.

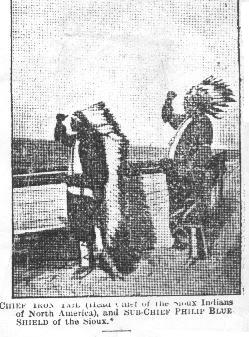

Iron Tail was however able to continue to England, although he walked with the aid of crutches for a time and it is suspected that for the first few weeks he took no active part in the show. Thereafter, he took his place as the ‘Head Chief of the Sioux Indians of North America’7.

Iron Tail wrote a letter from Exmouth, Devon, dated Friday, 27th May 1904, to Major J. R. Brennan, Agent at Pine Ridge, testifying to how well the Indians were being taken care of. Two days later, he was included in a group of eleven Indians photographed at Land’s End, Cornwall, on Sunday, 29th May 1904.

The photograph featured at the top of the page probably dates to the 1904 tour; the architecture appears distinctly Scottish. While the show was in Fraserburgh, Aberdeenshire, on 30th August 1904, Iron Tail was one of nine war-bonneted figures photographed on the rocks below the Wine or Aric Tower.

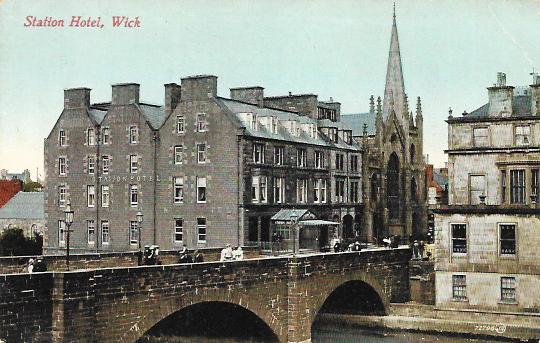

The Station Hotel, Wick

On the following Saturday, 3rd September, he and Philip Blue Shield were escorted by Frank Small on a rail trip from Inverness to Wick. After lunch in Randall’s Station Hotel, the excursionists completed the remaining eighteen miles of their journey in a hired carriage, for the purpose of complementing the Land’s End image with publicity photographs of the two Indians at Great Britain’s northernmost extremity, John O’Groats.

Prints of the John O’Groats photos are hard to come by but this one, featured in the Ardrossan & Saltcoats Herald on 16th September 1904, is an early example of a photograph reproduced in a Scottish newspaper.

Iron Tail had no sooner returned to the United States than he accompanied Buffalo Bill on the trail of a gang of robbers who had held up the First National Bank in Cody, Wyoming, on the afternoon of Tuesday, 1st November 1904.8 The extent to which the ensuing manhunt was a publicity stunt remains unclear. In an interview, Cody introduced his sidekick as ‘my old Indian scout, Sioux chief, Iron Tail’9.

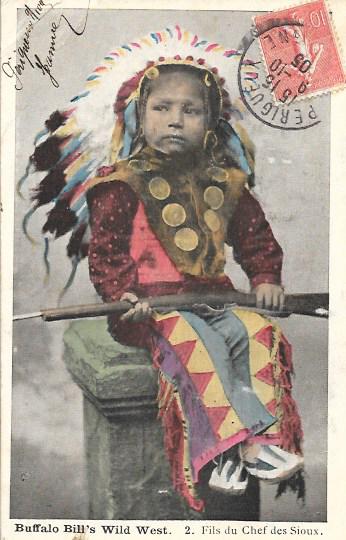

Iron Tail and his wife and son, depicted on a picture postcard issued in France, 1905

Iron Tail’s name was translated as Queue de Fer during the French tour of 1905. He returned to the United States with the main body of the company at the end of the season, on board the Fürst Bismarck, sailing from Genoa on 14th November 1905 and arriving at New York on the 29th. He was listed as 52, male and married. Listed together but separately from him were Mrs Iron Tail, 36, female, married; and Iron Tail, 5, male, single. It is surmised that the little boy was Edward Iron Tail, entered in the 1910 census as seven years of age. On the Italian dates of the 1906 tour of Europe, his name was rendered Coda di Ferro. Arriving from Antwerp, Belgium, at New York on 2nd October 1906, on board the S.S. Zeeland, Iron Tail, 55, his wife, aged 53, and the little boy presumed to be his son, again aged 5, were listed consecutively. It is noted that the wild variations in ages given are entirely typical of entries pertaining to Indians.

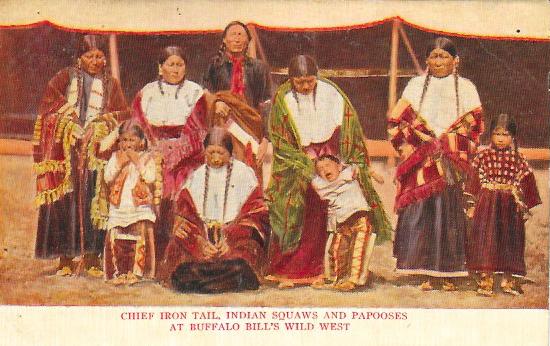

Edward Iron Tail, depicted on a picture postcard issued in France, 1905

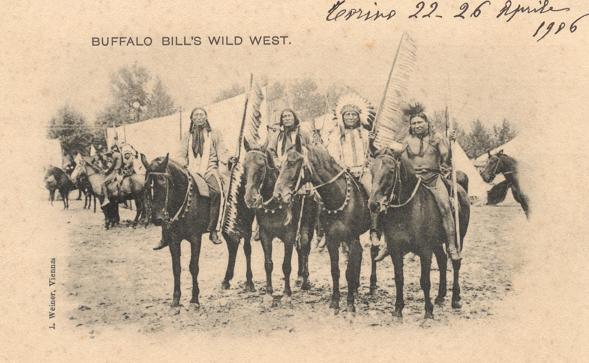

Four horsemen of the Apocalypse, Iron Tail to the left

Performing in New York in 1907, Iron Tail and Rocky Bear shared their recollections as veterans of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, otherwise Custer’s Last Stand10, in an interview with the New York World11.

One feature carried photographs of Iron Tail, absurdly and inexplicably paraded as ‘chief of the Pottawatomie Indians’12, at the wheel of a motor vehicle. At Guthrie, an arrangement had been entered into that Iron Tail would drive Mayor Brand Whitlock’s Pope-Toledo into the arena, loaded with Indians. It was further proposed that a second vehicle, carrying cowboys, would then attack the Indians. It was a matter of general though unaccountable disappointment that this absurd scenario had to be abandoned, owing to a severe rain storm.

Buffalo Bill’s right hand man, Tuesday, 2nd July 1907

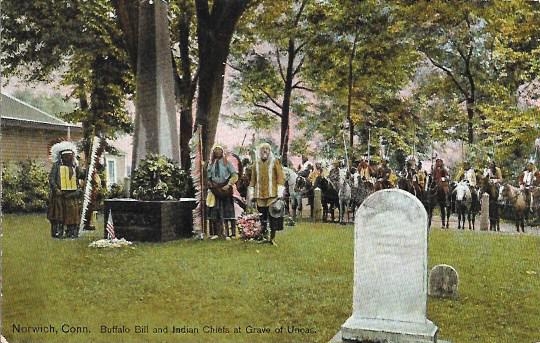

The above ‘Official Souvenir Post Card’, issued to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the founding of the town of Norwich, Connecticut, and the 125th anniversary of its incorporation as a city, is postmarked 6th July 1909.

Further explanation is found in an entry in the local paper, which runs:

Amuse your friends with a picture

puzzle characteristic of Norwich,

“Buffalo Bill with Chiefs Iron Tail

and Rocky Bear at Uncas Monument.”

On Sale today at 10c each.13It might reasonably be surmised that the photograph upon which the design is based can be dated to 2nd July 1907, then Buffalo Bill’s most recent visit to Norwich:

Visit Unca’s Grave. Norwich, July 2.- About sixty Indians travelling with a wild west show visited the grave of Uncas, the last of the Mohicans to-day and chanted Indian songs.14

Quod erat demonstrandum.

The visit was probably intended to forge a connection in the public imagination to the novels of J. Fenimore Cooper. Cooper had drawn upon the real-life Mohegan sachem for the name of his central character in The Last of the Mohicans.

Iron Tail’s family unit was listed in the 1910 census as residing on the Pine Ridge Reservation, in the Wakpamini (Agency) District of Shannon County, South Dakota, numbered as family 38 in order of visitation. Iron Tail’s age was entered as 56, his wife, Red House, 53 and his son, Edward, 7. The places of birth of the two adults and that of their parents was unknown but Edward was stated to have been born in South Dakota. None of them could speak English; the language spoken was given as Oglala. Iron Tail’s occupations were entered as ‘Laborer’ and ‘Showman’. It is presumed that Red Horn and Red House refer to the same woman; a third variant, Red Horse, is also encountered.

The statement that Iron Tail was Sitting Bull’s grandson15, is considered incredible even by the standards of Buffalo Bill’s notoriously mendacious publicity machine.

In spring of 1913, Iron Tail’s iconic status was further assured when the U. S. Treasury issued a newly designed nickel (five cents) coin, depicting twin aspects of the disappearing West, a buffalo on one side and an Indian profile on the other; much was made of the circumstance that A. Phimister Proctor’s bronze sculpture of Iron Tail’s head was at least one of the sources on which the latter image was based.

Iron Tail remained a fixture in Buffalo Bill’s ever-evolving show until its collapse at Denver in July 1913. For the next two seasons, Buffalo Bill made his way with the Sells-Floto Circus but Iron Tail was immediately snapped up by the Miller Brothers, who placed him on a five-year contract to their 101 Ranch.

It may be that, for Iron Tail, his investment in the show business was a favoured route to acculturation:

One of the best examples of the adaptation of modern facilities and customs by the American Indians is Chief Iron Tail, once the head of a powerful Western tribe, whose profile adorns the new five-cent piece recently issued by the government. Far from being down-trodden and disconsolate at the loss of his former power and glory as the leader of an important people, Chief Iron Tail has welcomed the innovations which make for the supremacy of the United States among nations of the world, and has availed himself of every opportunity to improve the conditions under which he and his tribe live. Chief Iron Tail is a very successful farmer and the proud possessor of an Overland automobile, several of which cars are in use in carrying on the business of the great ranch on which he lives. His greatest delight, between intervals of looking after his various business interests, is to gather a crowd of his redskin neighbors and take them for long rides through the Oklahoma prairie country. He is an expert driver and is never so happy as when sitting at the wheel of his Overland, speeding here and there over the territory he formerly traversed at the head of a war or hunting party of his fellows.16

It would of course be very interesting to know just how much of this account is actually true. Once again, his political status amongst his people is greatly exaggerated and the reference to Oklahoma seems questionable in the extreme. The 1910 Census had given no confirmation of the material success so graphically depicted here. However, another article, based on the same materials, specifically stated:

Chief Iron Tail, with many of his followers, now lives on the big 101 ranch, in Oklahoma.17 The two friends were reunited for one final, fatal season when a merger between Buffalo Bill and the Miller Brothers was announced in the spring of 1916. Iron Tail was once again thrust into the spotlight, when ‘veteran historian of the west’ John M. Burke placed a thoroughly garbled press release:

In the Indian contingent is the old Sioux chief, “Iron Tail.” He was a member of a band which Buffalo Bill, guiding Gen. Eugene A. Carr, defeated and almost annihilated in the battle of Summits’ Spring, in 1869. This battle was one of the most dangerous and important in the history of the central plains, and was the occasion on which Colonel Cody, single-handed, vanquished the Sioux chief, “Yellow Hand.” Gen. Carr, Scout Cody and the command received a vote of thanks from the territorial legislatures of Nebraska, Kansas and Colorado. These two old foes, now friends, Buffalo Bill and “Iron Tail,” will both be here with the reconstructed Wild West show, which opens its season here Friday, remaining two days. There will be a street parade each morning, starting from the camps at 10:30 o’clock.18

One is left to ponder whether historical objectivity still held any place in the Wild West camp, if indeed it ever had done to begin with. Yellow Hand - a notorious mistranslation of Yellow Hair - was a Cheyenne, not a Sioux, and in any event his legendary demise, allegedly at Cody’s hand, had come in 1876. Cody’s supposed victim at Summit Springs in 1869 had been another Cheyenne, Tall Bull. Two separate incidents, already much embellished, were now conflated. It is unlikely that Iron Tail’s part in either was anything more than a temporarily convenient piece of revisionism. The ‘two old foes, now friends’ motif reveals that Iron Tail was but the latest substitute for Sitting Bull and a distant echo of the glory days of the 1885 tour, on which the long-dead Hun’kpapa chief had been an actual participant.

A few weeks later, Iron Tail contracted pneumonia, and was admitted to St Luke’s Homeopathic Hospital, at Philadelphia, where he was treated by Dr Frederick Wilcox. When asked how old Iron Tail was, Dr Wilcox replied:

When he came here, he gave his age as 65, but from what I learned later he was nearer 95 years old. He was remarkably well preserved and stood his age well.19

Although there are minor variations in the ages given for Iron Tail in the official records, the opinion attributed to Dr Wilcox in this respect is not credible. From either Philadelphia or the next stand, Washington, D.C., Iron Tail was placed on board a passenger train bound for Fort Wayne, Indiana. There are conflicting reports of the precise sequence of events thereafter. According to the Omaha Daily Bee20, Iron Tail begged to be allowed to return home to die beside his wife. The Daily East Oregonian21 contradicts this version, stating that he was found dead on arrival at Chicago, after, on 29th May, Willard R. Godley, depot passenger manager at the Union State, had entered the coach to find the disconsolate widow sitting by his body. The former of these articles contains internal inconsistencies as well as obvious inaccuracies and, some of the specific details concerning Dr Wilcox aside, is considered the less plausible.

Buffalo Bill, whose own time was fast running out, is said to have mourned Iron Tail like a brother.

As highlighted by Richard Green22, the war bonnet in which Iron Tail was so often photographed now forms part of the collections of the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave, Golden, Colorado; another such item, acquired by Dr Colin Taylor from Tex McLeod in 1955, now in the collection of the Hastings Museum, Sussex, England, has proven rather more problematic in terms of its asserted Iron Tail provenance.

Iron Tail’s grave

Footnotes:

1 The Sitting Bull Surrender Census (Pierre: South Dakota State Historical Society Press, 2010), p. 142, footnote 87. The significance of ‘Wakpamni’ is ‘agency’.

2 “I dreamed of the elk”: Iron Tail’s muslin dance shield; Whispering Wind, Issue #266 / Vol 38 # 4

3 Colin Taylor, North American Indians - A Pictorial History of the Indian Tribes of North America (Bristol: Parragon, 1997), p. 85

4 Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors - A Photographic History by Gertrude Käsebier (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 2007), p. 32

5 St Paul Daily Globe, 13th August 1900

6 Washington Evening Times, 25th April 1901

7 Ardrossan & Saltcoats Herald, 16th September 1904

8 San Francisco Call, 2nd November 1904

9 Washington Evening Star, 2nd November 1904

10 25th June 1876

11 Reproduced in Watson’s Weekly Jeffersonian, 11th July 1907

12 Guthrie Daily Leader, 9th September 1907

13 Norwich Bulletin, 26th June 1909

14 The Daily Morning Journal and Courier (New Haven, Conn.), 3rd July 1907

15 Los Angeles Herald, 17th October 1910

16 Washington Herald, 22nd June 1913

17 Newark Evening Star, 3rd July 1913

18Detroit Times, 3rd May 1916

19 Omaha Daily Bee, 19th June 1916

20 19th June 1916

21 17th June 1916

22 Iron Tail’s Warbonnet in the Buffalo Bill Museum, Lookout Mountain; Whispering Wind, Issue #267 / Vol 38 # 5