| Home Links Contact |

| 1887-88 1891-92 1892 1902-03 1904 |

|

|

by Sam A. Maddra (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006)

Review by Tom F. Cunningham

Who would have thought that dancing could make such trouble? We had no wish to make trouble, nor did we cause it of ourselves. There was trouble, but it was not of my making. We had no thought of fighting; if we had meant to fight, would we not have carried arms? We went unarmed to the dance. How could we have held weapons? For thus we danced, in a circle, hand in hand, each man’s fingers linked in those of his neighbor.

– Short Bull, c. 1906

Hostiles? is the book version of a Ph.D. thesis by Dr Sam A. Maddra, a Lecturer in American History at the University of Glasgow. Ironically, however, it appears not to have been so well received in the United Kingdom as it deserves to be and, once again, I had to order my copy from the United States.It is of direct interest to me since overlapping considerably in subject matter with the first half of my book, ‘Your Fathers the Ghosts’; it recounts the story of the military suppression of the Ghost Dance movement and the subsequent fate of twenty-three of the participants imprisoned at Fort Sheridan, Illinois. However, in contrast with my own work, the three chapters dealing with the Indians’ experiences on tour in Europe with Buffalo Bill are thematic rather than strictly chronological in character.

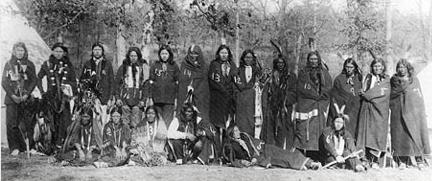

Nineteen of the twenty-seven Fort Sheridan prisoners. Kicking Bear is the irate-looking man seated in the centre, while the far more relaxed Short Bull reclines to his immediate left.As might be expected from a book of this nature, it is both original and academically respectable. Such a splendid reference work is certain to prove invaluable to other researchers in the same field. The bibliography is extensive. With the discipline of the true professional historian it founds directly upon the primary sources; particularly impressive and groundbreaking use is made of a substantial volume of archived official correspondence. I would however venture to suggest that the sources consulted are far from exhaustive and that the failure to consult the passenger lists for Buffalo Bill’s various transatlantic crossings constitute one particular glaring omission.

The central thesis challenges the accepted view – the ‘perversion myth’ – that the Ghost Dance religion initiated by the Paiute mystic Wovoka assumed uniquely militant overtones among the Lakota. It is argued that anthropologist James Mooney’s seminal study of the causes of this movement, published in 1896, is severely flawed to the extent that his Lakota informants were drawn exclusively from the ranks of the bitterly opposed ‘progressives’ actively engaged in the movement’s suppression, whether as reservation policemen or as army scouts. (Those who were best qualified to comment, the leading Ghost Dancers such as Short Bull and Kicking Bear, were in Europe with Buffalo Bill by the time Mooney came calling on the South Dakota reservations.) A further consideration is that for fear of reprisals, people from the Ghost Dance faction were reluctant to express their opinions openly.

Lakota use of ‘ghost shirts’, which supposedly rendered their wearers impervious to bullets, is widely cited as conclusive evidence of the Indians’ belligerent intentions but on a proper examination it appears that their adoption was entirely consistent with a programme of passive resistance. The shirts can also be interpreted as a purely defensive measure, intended to shield the dancers against the very real (and actually realised) threat of violent interference with the exercise of their religious liberty.

The Ghost Dance was and continues to be generally misunderstood as more or less synonymous with the war dance, or at the very least as a ritual preparation for a general Indian uprising. As Dr Maddra demonstrates, the hard evidence in support of this perception is conspicuous by its absence.

Dr Maddra places a great deal of reliance upon five Short Bull narratives, recorded on various occasions between 1891 and 1915. These accounts of his pilgrimage to Nevada and subsequent involvement in the movement substantiate her interpretation of the Ghost Dance cult as an indigenous adaptation of the Christian religion, with its central tenets having unmistakably been absorbed over a period of time from missionaries representing a range of denominations. Only in respect of its rituals and other outward manifestations was it traditionalist and nativistic. Dance is seldom, if ever, an element of worship in any of the orthodox branches of the Christian faith; duly considered the Ghost Dance represented a sincere attempt to adopt and adapt to the dominant culture’s spiritual worldview, on terms readily accessible to the Indians, with a stress upon the apocalyptic dimension which by the late 19th century was no longer routinely emphasised. It was surprisingly pacifistic in its content and on sober analysis was probably no more than a portal through which the Indians sought to resign themselves to the radical and rapid cultural transition taking place in their time and over which they otherwise held no control.

However, Dr Maddra’s emphasis upon Short Bull is at the expense of the other Indians and the central figure of Kicking Bear in particular is reduced to little more than a peripheral player. This is related to a further key weakness, in that the desultory fighting which followed in the wake of Wounded Knee receives no more than a passing mention. Black Elk recounts how he rode to the sound of the firing and led a charge of about twenty Lakota warriors upon the soldiers.1 Later on the same night when the Indians launched an ill-conceived assault on the Drexel Mission, Kicking Bear, in a classic Lakota battle manoeuvre, drew the hated 7th Cavalry under Colonel Forsyth into an ambush. Trapped on low ground, the soldiers watched in abject dread as the mounted Lakota warriors appeared on the ridges, surrounding them on all sides. Only the more or less fortuitous arrival of reinforcements prevented Kicking Bear from engineering what would otherwise probably have come to be known to posterity as ‘Forsyth’s Last Stand’.

The significance of these engagements ought certainly to have been evaluated and considered as the most obvious potential objection to her pacific interpretation of the movement. The mood clearly disclosed by the testimonies of the various Indians directly involved, including the Short Bull manuscripts upon which she otherwise places so much reliance, tends to indicate that the Indians had no appetite for fighting prior to the slaughter at Wounded Knee but in its aftermath were animated by the desire for revenge. This appears to be close to Dr Maddra’s own understanding when, in a masterly concluding paragraph she observes:

It (the Ghost Dance movement) became a resistance movement only when the government tried to suppress it.2 If only she had raised the same point earlier in the book and cared to elaborate upon it...

Showman Buffalo Bill Cody was not least among those holding a vested interest in the misrepresentation of the Ghost Dance as something far more sinister than it actually was. The mirage of one final Indian war presented him with an almost unimaginable and unforeseen publicity coup with which to fuel his 1891–92 season and - to a limited and ever diminishing extent - subsequent tours as well.

For Buffalo Bill, the unrest on the western plains during that fateful winter of 1890–91 was providential in a further sense. His Wild West show was in deep trouble. It was widely perceived as running directly counter to Allotment and Assimilation, the then prevailing Indian policy. A concentrated and accelerated programme was in place to remake the Indians according to an idealised and essentially fictitious image of white American society, with the mass of the people working on settled farms. Agriculture was not only alien to the traditions of the Indians of the Great Plains, it was also effectively impracticable under the extreme climatic conditions of the Dakotas.

Powerful interests were alarmed at official tolerance of the employment of Indians – the wards of government – by Buffalo Bill and other Wild West showmen of the time. Such activities represented a dangerous distraction from the assimilation programmes and encouraged the Indians to resume their traditional nomadic lifestyle as well as perpetuating the old ways. The freely available temptations in the great cities of the east and Europe were deemed a seriously demoralising influence. In the minds of their ‘benefactors’, principally the impossibly paternalistic Indian Rights Association, the fact that the shows provided the Indians with a rare opportunity to earn the means of supporting themselves and their families and thus to escape from total dependence upon the precarious goodwill of the federal government seems to have been no more of a consideration than the desires and aspirations of the Indians themselves.

The knives were out for Buffalo Bill. For a time, it seemed a foregone conclusion that officialdom in Washington would accede to irresistible pressure and that the Secretary of the Interior’s ban upon the employment of Indians in shows would be made permanent, thus surely spelling the end for the Wild West.

Matters came to a head when small parties of disaffected Indians began drifting back early from the tour of continental Europe in June 1890, telling tales of systematic cruelty and neglect. One man who made it no further than New York City was Kills Plenty, found to be suffering from a severely injured wrist, sustained when his horse fell on him in the arena. When he was admitted to hospital, it was found that blood poisoning had set in and that he was further weakened by tuberculosis. Kills Plenty died on the night of 18th June 1890 and his body was sent back to South Dakota for burial, at Buffalo Bill’s expense.

Kills Plenty was not the only fatality. At least seven Indians failed to survive the 1889–90 tour, in consequence of diseases and mishaps of various kinds – Wounds One Another fell from a train in Germany. Others returned with permanently shattered constitutions. The protests of the objectors were raised to a full crescendo of outrage but however shocking these statistics might appear, there was a definite semblance of hypocrisy, for conditions on the reservations during this same period were so bad that the mortality rate there was similar and if anything even worse. Dr Maddra makes a key point when she pertinently observes:

Similar accusations of mistreatment and neglect could just as easily have been laid against the government itself.3 Colonel Cody was recalled from Europe, along with his entire Indian contingent, to answer the allegations which had been laid against him. After various hearings, the Washington authorities were eventually satisfied with his defence.

A curious inversion now manifested itself. Quite fortuitously, the main body of the Indians, apparently loyal to Buffalo Bill and without complaint about the treatment they had received from him, arrived back on Pine Ridge reservation right on cue for the serious troubles which erupted from November 1890 until the middle of January 1891. Probably to everyone’s surprise, almost to a man they took the side of the government against the ghost dancers, enlisting as scouts and reservation police. These same men played an indispensable part in the restoration of a negotiated peace through the inevitable surrender of the ‘hostiles’ on 15th January 1892, at the same time procuring the Wild West’s redemption.

Having witnessed the strength and permanence of the white man’s world for themselves, these men had grasped the futility of continued resistance. A further motivation was that they did not wish to jeopardise their chosen livelihood and were therefore as anxious as anyone to lift the threat to the continued sustainability of the Wild West show.

Buffalo Bill was no longer swimming against the tide. The military and political establishment had grasped that the Wild West, for all the ostensible unredeemed savagery of its Indian performers, was nonetheless a powerful force for their civilisation. Against all previous expectations, Buffalo Bill was encouraged to return to Europe with a fresh company of Indians, amongst them twenty-three of the twenty-seven hostages held at Fort Sheridan. It was anticipated that the tour would have the same civilising effects which the experience had exerted upon their predecessors and, in addition, the opportunity to put the principal mischief-makers well out of harm’s way was unanswerable. A further consideration was that the former inmates of Fort Sheridan could now earn a living for themselves and their families, instead of having to be maintained indefinitely at government expense.

Nonetheless, the howls of protest from the ‘Reformers’, who continued to demand the permanent suppression of the Wild West show, were still ongoing even after Buffalo Bill and his company were in mid-Atlantic and thus beyond all practicable prospect of recall.

It has to be remarked that Dr Maddra’s selection of photographs is somewhat pedestrian and that this inevitably limits the impact of her work. Of sixteen images, eleven were obtained (or at least readily available) from the Buffalo Bill Center of the West (formerly the Buffalo Bill Historical Center) and of these four were extracted from the official programme for the 1891-92 season. There are several other images which I suspect she would like to have had, for example the studio photo of Kicking Bear in Glasgow which has recently come to light but which she was presumably unaware of. However, I have no doubt that the photograph of Short Bull in his later years (c. 1909), dressed in a ghost shirt (this provides the cover image), which she acquired from the Museum für Völkerkunde, Hamburg, answers her purposes ideally and therefore represents a coup upon which it would be churlish not to congratulate her.

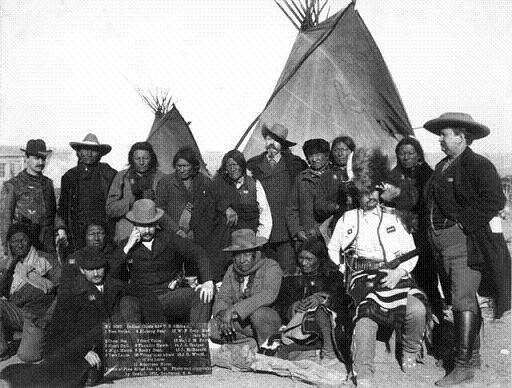

Difficulty arises in connection with the Pine Ridge photograph (infra) taken by Grabill on the day following the surrender and included in the graphics for Hostiles?. In the group are various key players, including prominent Indians from both sides of the traditional/progressive divide, as well as Buffalo Bill Cody and his general manager, John M. Burke. Also included in the group is newspaperman George C. Crager, who later enlisted as one of the Lakota interpreters on the 1891-92 tour and was a shadowy but generally omnipresent figure throughout the entire affair.

Pine Ridge, 16th January 1891

Sitting to the right is a figure modelling various items from Crager’s collection of Indian artefacts. Dr Maddra uses this image in both Hostiles? and her earlier booklet, Glasgow’s Ghost Shirt, but quite incredibly in neither appears to remark that the beaded waistcoat is the identical item which just one year later was acquired by Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Museum. Maddra identifies the sitting Indian immediately next to the model as Kicking Bear but this is extremely suspect. In the above version of the same print, some of the Indians are numbered, and a plate with names on it is included. The man whom she identifies as Kicking Bear is number 8, but number 8 according to the plate is Thunder Hawk. I would respectfully suggest that the ill-humoured Indian to the extreme left, whom Dr Maddra misidentifies as Thunder Hawk, is in fact Kicking Bear. Notice that his outfit appears to consist of white men’s hand-me-downs, and it is a far cry from the flamboyant costume which he would wear in the Wild West arena a few months later. The Indian in the broad-brimmed hat standing second from the left is Chief Rocky Bear, a ‘progressive’ recently returned from the tour of Europe, and he is clearly doing very well for himself. The apparent reason why it has proven difficult to identify some of these figures is that their features are distorted by the low January sun in their faces, as evidenced by the very narrow shadows under the brims of those wearing hats.

The book is to some extent devalued by a number of significant errors of fact encountered at various points in the text.

The first of these relates to the number of Indians involved in the 1891 tour. That twenty-three out of the twenty-seven Fort Sheridan prisoners chose to accompany Buffalo Bill to Europe as an alternative to continued incarceration is not open to doubt. Dr Maddra is reasonably successful in charting their subsequent comings and goings.

However, she is far less concerned to keep track of those who voluntarily enlisted at Pine Ridge and serious difficulties arise over their numbers. The synopsis on the front inside cover informs us that in addition to the twenty-three prisoners, there were ‘forty-six other Lakota Indians’ (yielding an aggregate of sixty-nine). We have progressed no further than the first page of the introduction when this figure is without explanation commuted to ‘a further forty-two Lakota Indians’ (total sixty-five). In the opening sentence of a mildly disastrous Chapter Six4, Dr Maddra gives the aggregate number of Lakota participants as seventy-five. These figures are transparently based on three separate and mutually contradictory sources. It is respectfully submitted that each represents a distinct phase of her research and that she has failed to identify and resolve these glaring inconsistencies as her mastery of the subject has advanced.

In footnote5 to the passage in which she advances the third of these figures, Dr Maddra takes Don Russell and Rosa & May to task for having submitted the (admittedly) grossly exaggerated total of one hundred Indians. There is a touch of unconscious irony here, given that she gets it so badly wrong herself.

As she admits in footnote6, there are two prisoners whose return to the States she has not been able to account for, Coming Grunt and Crow Cane.

As regards the latter, it would appear that Dr Maddra has missed a reference in a letter (cited by her elsewhere) from Captain Penney, Acting US Indian Agent at Pine Ridge, dated 22nd August 1891, in which he acknowledged the safe arrival of Long Wolf, Bone Necklace and a third Indian at Pine Ridge on the previous day. The first part of the third Indian’s name is ‘Crow’, and the second part is inconveniently smudged and thus illegible. There was only one other Indian, Charging Crow, who had ‘Crow’ in his or her name, and he is known to have remained with the company until the close of the Glasgow season. That this in fact refers to Crow Cane is established by the evidence of the relevant passenger list and is therefore a full resolution of the difficulty.

Regarding Coming Grunt, I can add only that his presence in Glasgow is attested in a letter from Cody to the Acting Indian Agent at Pine Ridge, dated 16th January 1892. He was identified as the son of Two Bulls and stated still to be with the company at that time. How much longer he remained has yet to be established, as his name does not appear on any of the subsequent passenger lists which have thus far been identified.

There is an apparent case of mistaken identity:

Clifford was later employed by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West as the show’s orator when it toured Britain in 1891-92.7 Dr Maddra is referring here to Henry Clay Clifford (1837-1906), an American known as Hank, in connection with his role in conducting the mortal remains of an Indian, Kills Plenty, back to Pine Ridge. The orator during 1891-92 was Henry Marsh Edsall Clifford (c. 1847-1924), an English actor. These are quite certainly two distinct individuals. That they shared the same first and last names appears to be an absolute coincidence.

Further problems arise when she states:

The exhibition was “organized around a series of spectacles which purported to re-enact scenes portraying different ‘Epochs’ of American History.” Following the “Primeval Forest,” peopled only by Indians and wild animals, the story of conquest was portrayed.8 This is fundamentally wrong. What she is referring to is the indoor version of the show, which, on the 1891-92 season, was produced in Glasgow alone. At all the preceding (outdoor) English and Welsh venues, the programme consisted of seventeen scenes from the Wild West, which were not arranged in any particular chronological or narrative order and categorically did not include the ‘Primeval Forest’ sequence in any shape or form.

Just five pages later she duly acknowledges:

When the exhibition traveled north to Glasgow for the winter season, Nate Salsbury revived Steele Mackaye’s indoor pageant “The Drama of Civilization,” which was originally written for the Wild West show when it performed at Madison Square Garden in New York.9 The Drama of Civilization was precisely the version of the show which had been described in the first of these two passages. As well as being a narrative in six acts, commencing with the ‘Primeval Forest’, it made use of various special effects which were not practicable in the outdoor version of the show. A further bonus was a reenactment of ‘Custer’s Last Stand’, which had not featured in the outdoor venues.

Fundamental concerns also arise in connection with the following statement:

Until March 1891 there was no assurance that the Indians would be allowed to return to Europe, and as their role had been at the core of the show, management had to be prepared for a drastic reorganization. Salsbury had put into effect his idea of a show that “would embody the whole subject of horsemanship,” and had recruited equestrians from around the world, creating what was to become known as the Congress of Rough Riders. Cody’s success in obtaining the required Indian performers meant that the new show delayed its debut until Buffalo Bill’s Wild West returned to London in May 1892.10 This is extremely dubious. Of the two sources she cites for this, one is Don Russell, The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill:

As organized in 1891, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West had 640 “eating members.” There were 20 German soldiers, 20 English soldiers, 20 United States soldiers, 12 Cossacks, and 6 Argentine Gauchos, which with the old reliables, 20 Mexican vaqueros, 25 cowboys, 6 cowgirls, 100 Sioux Indians, and the Cowboy Band of 37 mounted musicians, made a colorful and imposing Congress of Rough Riders.11 This disastrous but generally accepted passage of Russell’s is simply wrong; it is of value only as an indicator of the continuing deplorable state of American ‘scholarship’ on the 1891-92 season. That Dr Maddra, who of all people certainly ought to have known better, has relied upon it frankly beggars belief.

An entire legion of US writers have uncritically founded upon this passage, relying upon Russell, whose writings are for some reason accorded canonical authority. In point of fact, as anyone making even a superficial attempt to research the primary sources for the 1891-92 season would very quickly discover, there were no German soldiers, there were no Cossacks, there were no Gauchos, and there were no English Lancers until the middle of January 1892. ‘Cossacks’ (actually ethnic Georgians from the Caucasus) and Gauchos were introduced while the 1892 London summer season was underway but the Congress of Rough Riders of the World banner was not launched until 1893, during the World’s Fair season in Chicago. (It may well be that it is the 1893 season that Russell intended to refer to, not 1891.) An added irony is that it is precisely this same passage which is elsewhere held up to ridicule by Dr Maddra for the ill-informed statement that there were one hundred Indians on the tour.

Dr Maddra knows all this perfectly well and that is why she hedges her bets by modifying Russell’s position by adding the detail that Salsbury had conceived the Congress of Rough Riders during the period of uncertainty in the winter of 1890-1891 and that the debut of the new version of the show was delayed until May 1892. It may be that she is correct, insofar as the first part of this statement is concerned, but the meagre sources which she advances fall far short of supporting her conclusion.

The other source cited is L. G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933 12, which leads us back to the Russell passage, adding nothing more, so that it can scarcely be taken as corroborating testimony.

A distinct suspicion arises that Dr Maddra has unearthed such a wealth of information that she finds significant difficulty in marshalling her facts. Referring to the marriage certificate of mixed-blood Lakota interpreter John Shangrau and Lillie Orr, she recounts that:

Shangrau’s father, Jule, had been a stock raiser of French descent, and his mother, Mary, had come from the Smoke band of the Oglala.13 My own understanding of the entry relating to John’s mother is that Smoke was her father’s name and hence a substitute for a maiden name, not therefore necessarily the name of the band to which she belonged. A few pages further forward, the same thought appears to dawn upon Dr Maddra when she proceeds to consider the marriage which had taken place between Black Heart and Calls the Name in Manchester a few months before:

On the marriage certificate, Calls the Name’s father is given as Smoke, which indicates that she too was related to John Shangrau, who acted as witness.14 In the same context, she states that George Crager was the best man at the wedding. In fact, there are two separate newspaper accounts, one identifying Crager as best man, the other according this position to Shangrau. In the light of the familial and racial connections, Shangrau has to be considered the more likely candidate.

Elsewhere, Dr Maddra makes reference to Calls the Name’s ‘nephew Wm. Shangrau’15. William Shangrau was John’s brother but there is no indication that she has made the connection. In an interview with John Shangrau’s wife Lillie in the New York Herald16, it emerges that No Neck, who had also been present in Glasgow, was John’s uncle. Since it is known from other evidence17 that No Neck was Calls the Name’s brother, this final detail may be taken as settling the matter. Calls the Name was John Shangrau’s aunt.

Reference is made to ‘Luther Standing Bear, who traveled with the show when it toured Britain in 1903-04…’ 18 However, although Luther Standing Bear was indeed the Lakota interpreter on the 1902-03 season, he did not return in 1904 because of serious injuries sustained in a train crash in the USA.

Dr Maddra commits the rather odd error of claiming that a party of five Indians disembarking in New York from the Bremen steamship Saale on Saturday, 14th June 1890, had boarded the vessel in Leipzig19, a misconception which even a superficial inspection of a map of Germany should suffice conclusively to dispel. The actual point of departure was Bremen, which holds the essential qualification of being a sea port. The actual significance of Leipzig is that it was the venue to which Buffalo Bill was next headed.

Recounting the story of the Indian who attempted to stay behind in Aston because he wished to set up home with a local girl he had met but was obliged to rejoin the entourage, Dr Maddra places the scene of the action not in Birmingham but in Leeds. If I may say so, that she – a Yorkshire native herself, so I understand - should commit such an error is quite ‘Aston-ishing.’20

A similarly nebulous grasp of English geography manifests itself once again in an erroneous detail appearing in connection with the marriage of Black Heart and Calls the Name. Dr Maddra refers to the ‘Parish of St. Brides, Stafford, County of Lancaster’21 - this should be Stretford.

Nor does she fare much better with her adopted home city of Glasgow:

When Buffalo Bill’s Wild West travelled north to Scotland for its five-month winter stand in Glasgow…22 This is decidedly careless. The show opened on 16th November 1891 and closed on 27th February 1892, an interval of a little over three months. Probably she had in mind the total period of time which the show or at least a part of it was located in Glasgow but if so this could have been expressed with greater precision.

She also claims that:

The marriage (of John Shangrau and Lillie Orr) took place before Sheriff Spens at the County Buildings in Glasgow’s East End on 4 January 1892.23 The complex of structures formerly known as the County Buildings is not located in the East End but in the heart of the central district known as the Merchant City. Incidentally, it is not quite correct to state that the marriage took place before the Sheriff. Dr Maddra has not understood the legal technicalities involved. John and Lillie were married by declaration, one of the three irregular forms of marriage peculiarly known to Scots law at that time. The actual ceremony, such as it was, had taken place in Castle Street. The specific purpose of the appearance before Sheriff Spens was to obtain a warrant for registration.

A similar difficulty arises when she refers to Charging Thunder being brought before the ‘Eastern Police Courts’24 on a charge of assault. This should actually be the Eastern Police Court (singular), which was located in Tobago Street. The Police Courts were, loosely, precursors of the District Courts, although there is no precise modern equivalent.

Dr Maddra cites a statement made in Science Siftings25:

It is strange, but an actual fact, that the Manadad (Dakota) Indians use a Welsh dialect. At the present day a Welshman can understand them. It is presumed and is backed up by tradition, that some Welsh pioneer got stranded among these Indians and taught them their language. The word ‘Dakota’ appearing by way of commentary in brackets appears in the original but it is somewhat concerning that Dr Maddra gives no sign of recognising ‘Manadad’ as an erroneous rendering of ‘Mandan’. The Mandan were a tribe, largely wiped out by a smallpox epidemic in 1837, of whom this sensational and questionable story has often been told.

Dr Maddra gives the date of the final performance in Glasgow as ‘28 February 1892.’26 The actual date was Saturday, 27th. My objection might seem like splitting hairs but the discrepancy has awkward consequences. Nate Salsbury, in a letter dated the 29th, told of how ‘only last night’ Kicking Bear had launched into an unscheduled narration of his deeds of valour and one has therefore to question whether this incident actually took place in the arena, as Dr Maddra, following L.G. Moses 27, supposes. It may well be that this was indeed the case - assuming that Salsbury’s chronology was defective - but it does not appear to be warranted by the sources.

Perhaps the foremost value of Dr Maddra’s thesis lies in the final chapter, which reviews the aftermath and adduces evidence in support of her claims that Kicking Bear made a second visit to Wovoka in 1902 and that, contrary to general belief, Kicking Bear and Short Bull continued to practise the Ghost Dance long after its military suppression and for the remainder of their lives, although obviously without provoking the disastrous consequences which had attended its first appearance.

Dr Maddra’s research was certainly ground-breaking and has opened up new fields of enquiry previously sadly neglected. However, as well as being her greatest strength, her originality is also her Achilles heel. It is quite obvious that her tutors lacked the specialist expertise which would have enabled them to comment constructively upon her subject matter and that it was therefore impossible to rectify a number of clumsy errors.

Hostiles? would have been a much better book if only the numerous errors of detail which mar it had been picked up during the production process. It is with due respect that I conclude that whilst setting the standards in most key respects, it is simply substandard in others.

Footnotes:

1 The Sixth Grandfather - Black Elk’s Teachings Given to John G. Neihardt, (Lincoln & London: Bison Books, 1985), p. 272

2 p. 189

3 p. 82

4 p. 122

5 Footnote 2, p. 247

6 Footnote 51, p. 263

7 Footnote 19, p. 235

8 At p. 123, quoting from Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation (New York: Harper Perennial, 1992), p. 67

9 p. 128

10 pp. 99 - 100

11 The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960), p. 370

12 p. 118

13 p. 142

14 p. 162

15 p. 172

16 22nd July 1894

17 See p. 162

18 p. 135. These same dates are repeated at p. 164.

19 p. 64

20 p. 143. Dr Maddra gives her source for this story thus – ‘Unidentified newspaper clipping, CS, MS6.IX, Box 2, McCracken Research Library, BBHC.’ The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post, 5th October 1891, one of a number of papers which reproduced the piece, attributes it to the Birmingham Mail. This little drama seems to have been enacted between Thursday, 1st October 1891, when the Indian returned to Birmingham, and Saturday, 3rd, when the officials of the Wild West caught up with him.

21 Footnote 41, p. 257

22 p. 153

23 p. 143

24 p. 165

25 p. 149. The date of the article was 30th July 1892, by which time the Wild West had returned to London.

26 p. 176

27 Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians 1833-1933, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), p. 119