| Home Links Contact |

| 1887-88 1891-92 1892 1902-03 1904 |

|

|

Don Russell, in an influential and widely-quoted paragraph (The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960, pp. 370-371), grandly misinforms us:

Where Russell obtained his information for this remarkable statement he unfortunately neglects to tell us. It is further regretted that this passage has been uncritically cited in one book after another, compounding serious and lasting confusion.

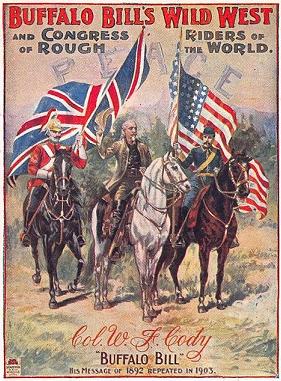

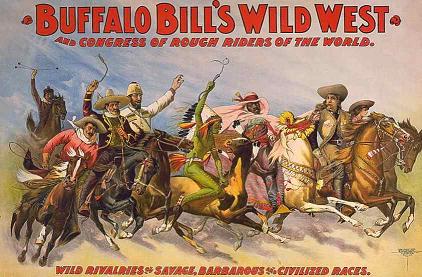

As organized in 1891, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West had 640 “eating members.” There were 20 German soldiers, 20 United States soldiers, 12 Cossacks, and 6 Argentine Gauchos, which with the old reliables, 20 Mexican vacqueros, 25 cowboys, 6 cowgirls, 100 Sioux Indians, and the Cowboy Band of 37 mounted musicians, made a colorful and imposing Congress of Rough Riders. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West did indeed eventually evolve into Buffalo Bill’s Wild West & Congress of Rough Riders of the World, an expanded, globalised concept merging the tried and tested core elements of the spectacular with military, predominently cavalry, displays from all points of the compass. A comparative perspective was made explicit as Colonel Cody reversed his original premise. Having previously taken the New World to the Old, he now undertook to entertain and enlighten the American heartland in a celebration of more ancient equestrian traditions betokening racial frontiers encountered overseas.

However, it is reasonably clear that Russell has erred respecting the timescale of this gradual metamorphosis. Television documentaries are likewise consistently vague in this respect and frequently appear to imply that these international elements had been featured by the show ab initio.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, as organised in the spring of 1891, remained a Wild West show pure and simple, whose human performers, with peripheral exceptions only, were cowboys, Indians and Mexicans, from the western frontier of the United States. Following an almost exhaustive study of the saturation press coverage and official programmes for the relevant period, I have failed to source a single reference to the international elements listed above. The four-page Programme Insert, 1891, printed by ‘Fred. R. Spark & Son: “The Leeds Express” Printing Works’ and transcribed here, is significantly different in its wording from the touring programme reproduced by Alan Gallop in Buffalo Bill’s British Wild West (Stroud: Sutton Publishing Limited, 2001), p. 168, and yet the two are clearly identical in terms of substance. Neither makes any mention of human performers other than American frontier folk.

The show format for the initial part of the Glasgow winter season of 1891-92 was The Drama of Civilization, Steele Mackaye’s pageant of the American West; it is hard to visualise what sort of contribution Germans, Cossacks and Gauchos could have made. The conveniently rounded-up figure of ‘100 Sioux Indians’ is likewise ill-informed; it is taken directly from the Wild West’s inflated advertising claims.

A fundamental change of direction would certainly have made perfect sense at this time, as the continuing supply of Native American performers was under threat following the catastrophic events of the previous season, over the course of which seven had died through a combination of disease and accidents, both in and out of the arena. No doubt, therefore, such an adjustment must have been in serious contemplation.

However, one of the very earliest occasions on which extraneous elements were incorporated into the Wild West came on the evening of 31st July 1891, when a benefit performance was given in Manchester, England, in aid of local Crimean War veterans.

In Glasgow, a new and experimental version of the show, boldly entitled A New Era in History, was unveiled before an invited audience on Friday, 15th January 1892, and to the general public from Monday, 18th, until the season’s conclusion on Saturday, 27th February. This involved ‘Stupendous Additional Attractions’, specifically a detachment of English Lancers, thirty members of the Central African Schulis tribe (not Zulus, as was later claimed) and a herd of six performing Burmese elephants.

For the London 1892 summer season, the show briefly reverted to its original and classic Wild West format, before the ‘Cossacks’ (actually ethnic Georgians), on Wednesday, 1st June, and Gauchos from the Argentine, on Thursday, 23rd, were introduced in separate stages.

Buffalo Bills Wild West & Congress of Rough Riders of the World was not unveiled under that name and in its concluded form until the Chicago World’s Fair season of 1893.

One small confirmation that the academic community is indeed in crisis over this particular issue is to be found in Sarah J. Blackstone’s Buckskins, Bullets and Business - A History of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (1986: Greenwood Press, New York). At page 26, she specifically states, drawing upon Russell, that twelve ‘Cossacks’ were among the new elements added to the show ‘in the spring of 1891’. For some reason that is not apparent, she felt unable to commit to a similar position concerning the Gauchos, stating merely that, six in number, they had been added by the time the show reached England. From the immediate context, which refers to the preceding venues in Belgium and Germany, this can only be taken as indicating June 1891. This position is underscored by footnote 22 (p. 370), in which she cites the Russell passage as authority (at the same time unfortunately raising the number of the Indian contingent to the implausible total of one thousand).

By page 81, however, she has changed her mind:

Russian Cossacks first joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in London in 1892. The original group numbered ten... Of the Gauchos, she then (and on this occasion correctly) pronounces:

South American Gauchos were added to the Wild West in 1892. These riders were recruited in Argentina and joined Cody in London. It appears undeniable that these two statements stand in open contradiction to what has gone before, in the very same volume. One strongly suspects that it is a case of Ms Blackstone having signally failed to marshall her sources. She ought to have drawn the obvious conclusion that Russell’s stated position cannot be reconciled to the primary sources.

The foregoing is consciously intended as a challenge; anyone in possession of actual evidence tending to substantiate the orthodox view, please do let me know.