| Home Links Contact |

| 1887-88 1891-92 1892 1902-03 1904 |

|

|

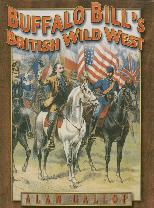

by Alan Gallop (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2001)

Review by Tom F. Cunningham

Alan Gallop is a prolific and accomplished author, with upwards of a dozen major works of non-fiction to his credit. What is even more impressive is that this voluminous literary output is but a sideline to an already distinguished career in journalism and public relations.

A superficial examination of Gallop’s titles tends to the impression that, as opposed to forming a progressive series of explorations on a central theme, they are mutually unrelated. For present purposes, his most alluring work by a considerable distance is the landmark 2001 publication, Buffalo Bill’s British Wild West, inspired by a coup de foudre experience graphically recounted in his preface.1

The commercial success of this immense contribution was both deserved and entirely predictable. A single systematic study of Buffalo Bill’s British venues was certainly long overdue and more than two decades down the line, it has to be questioned whether any serious challenger will ever emerge. It therefore necessarily takes its place as the indispensable foundation for further researches on the subject, themselves warranted only to the extent that they either build upon or else correct Gallop’s findings.

As correctly asserted in the sleeve notes, the book is ‘richly illustrated’; the author’s prodigious researches have indeed succeeded in building a wealth of photographic and other illustrative materials splendidly visualising the events meticulously detailed in the text. A further distinct merit is that it breaks with the dismal tradition, long established by the preponderance of pre-existing literature on the subject, of placing undue emphasis upon Season 1887-88, a trend which has always operated to the severe detriment of Buffalo Bill’s four subsequent visits to Great Britain.

That so much was achieved within a relatively short timeframe is undeniably meritorious but one is led to question whether Gallop’s greatest strengths are not also his foremost weaknesses. His unquestioned status as a pioneer in the finest Western tradition necessarily implies a certain difficulty in the matter of finding co-workers competent to provide constructive criticism. Besides, his very modus operandi, spending a couple of years at most on one project before moving onto another, means that he could never have hoped to attain the focused mastery which comes only through sustained long-term specialisation.

A related misgiving lies in the sheer size of the undertaking. Buffalo Bill’s British adventures in their entirety amount to rather more than can be conveniently accommodated within a single volume. This consideration is all the more acute for the substantial proportion of the book devoted to background material, or, as Gallop himself expresses it, events taking place ‘before, between and after the British tours’2.

I offer the following comments on specific statements, several of which I challenge as errors of fact.

We are informed that Wild Bill Hickok, an early associate in Buffalo Bill’s theatrical ventures, was paid off with a £1,000 bonus.3 We later discover that at the end of the 1885 season, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was £60,000 in the red.4 Should these pound (Sterling) signs not instead be dollars?

The native participants on the 1887 season are grouped in the tribal divisions of ‘Sioux, Cheyenne, Kyowa, Pawnee and Arapaho’5. The conventional spelling of the third of these designations is ‘Kiowa’. In point of fact, virtually or even actually all of the Indians on this tour were Lakota (Sioux). Buffalo Bill’s publicity machine routinely and perennially misrepresented his Indian performers as drawn from a far broader range of tribes than was ever the case. Similarly, Gallop cites a contemporary article according to which the Indians were ‘Sioux, Cheyenne… Pawnees and Raphoes’6. Like many others before and since, he has fallen for the standard deception. The official programme, incidentally, grouped the Indians into Cut off Band of Sioux, Araphoes, Cheyennes, Brule Sioux, Shoshones and Ogalallas.

Gallop appears to take Red Shirt’s advertised status as Sitting Bull’s second-in-command at face value.7 In point of fact, Red Shirt was a no-account Loafer band chief, practically unknown beyond his role as a show Indian. In the same context, he cites an odd yarn, bearing all the hallmarks of yet another patent fabrication from Cody’s publicity team, according to which Red Shirt had recently put down an uprising within the tribe. By 1887, all meaningful authority had for years been concentrated in the hands of the federal government, no tribal power remaining for rival factions to contend over.

Observing that the show arrived in Birmingham on 4th November 1887, Gallop claims that it gave its first performance there ‘two days later’8, by implication, 6th November. This position is made explicit on the following page:

The first performance (in Birmingham) took place at 3 p. m. on the afternoon of Saturday 6 November.9 This is repeated in an appendix10, when he gives 6th - 26th November as the dates for Buffalo Bill’s 1887 engagement at Birmingham’s Aston Lower Grounds.

In fact, 6th November 1887 was a Sunday. The record emerging from contemporary newspaper articles and adverts is unmistakably clear. It demonstrates, in open contradiction to Gallop’s statements, that the show first arrived in Birmingham on Wednesday, 2nd November 1887, before opening on Saturday, 5th, running for almost four weeks, until closing on Thursday, 1st December.

An Indian named Surrounded died of pneumonia in Salford on 14th December 1887, three days before the show opened there. Unaccountably, Gallop maintains that:

No record now exists as to what finally happened to Surrounded’s last remains.11 He further explicitly denies that the deceased was buried in London’s Brompton Cemetery, engaging in irresponsible speculation that Surrounded may have found his final resting place in an unrecorded, unmarked common grave in Salford. In fact, it is a matter of clear record, as established by an entry in the Brompton Cemetery Records, that ‘Surrounded (of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West)’ was indeed buried there on 15th December 1887.

Gallop states that there were ‘86 Indians’12 on the 1891 tour, including twenty-three prisoners of war from the Ghost Dance trouble. The latter figure is certainly correct but where he has got the overall total of eighty-six from is not at all clear. Press releases generally gave the impression that there were between seventy and eighty Indian performers but even this is inflated. It is unlikely that at any point on the tour the true figure ever exceeded sixty-six.

In the same context, Mash the Kettle is listed as one of the Indian performers in 1891-92. An Indian of this name was a protagonist in the opening phases of the Ghost Dance movement but his involvement on this or any other tour is extremely doubtful.

Gallop refers to ‘Two Strokes’13 but the name of this Brulé chief is more usually rendered as Two Strikes.

Gallop claims that in the late spring of 1891, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West crossed the German border into ‘Holland’14. The only European countries visited that season, prior to setting sail for England, were Germany and Belgium. There are no documented Dutch venues.

The battle sequence recreated on the 1891 tour was a re-enactment of the hand-to-hand encounter between Buffalo Bill and Cheyenne war chief ‘Yellow Hand’ - or, more accurately, Yellow Hair; this incident, alleged to have taken place at War Bonnet Creek, forms a major component of the Buffalo Bill legend. This was the - probably mythical or at least exaggerated - ‘First Scalp for Custer’ exploit, which, according to Gallop, took place in July 187515. This is in accordance with a considerable volume of Wild West publicity material, including the official programme for the 1891 tour, in which 17th July 1875 is frequently advanced. However, there is confusion here. The whole point of the story is that Cody, an army scout at that time, killed and scalped the Indian as revenge for the death of Col. George Armstrong Custer and it would be a strange thing indeed if he had done so almost a year before Custer’s downfall at the Little Bighorn. The date of the subsequent engagement at War Bonnet Creek, whatever exactly transpired on that day, was 17th July 1876. Gallop’s failure to detect this serious discrepancy is all the more embarrassing for the fact that he had already dealt with the same episode in one of his early chapters, setting out a resumé of Buffalo Bill’s career on the frontier, correctly giving the year as 187616. For good measure, in the same context, Gallop makes reference to ‘General’ Custer, ‘the daring and dashing leader of the Fifth (emphasis mine) Cavalry’17. This should, of course, be the Seventh.

Gallop makes mention of an Indian by the name of Bear Growls18 as one of those attending the funeral of Paul Eagle Star on Tuesday, 25th August 1891. His source is almost certainly the Nottingham Daily Express, 26th August 1891, but this stands in isolation and the name is not otherwise known. A journalistic error is strongly suspected; that any such Indian travelled with the company at this or any other time is unsubstantiated.

On the afternoon of Sunday, 27th September 1891, Cody and a party of Indians from the show put in an appearance at Temple Meads Railway Station, Bristol, to greet theatrical friends Henry Irving and Helen Terry and to speed them on their way ‘on their journey home to London.’19 In point of fact, the available evidence indicates that their actual destination was Birmingham.

Buffalo Bill had a protegée, a young American actress named Viola Clemmons, who, with his financial backing, briefly toured the theatres of England and Wales with a Western show of her own, The White Lily. Gallop’s useful treatment of this long-neglected subject20 was, at the time of publication in 2001, in a class of its own but its serious shortcomings have since been laid bare by subsequent scholarship.

Gallop claims that a dozen Indians were loaned out from the main touring party.21 This fails to take account of a party of ten separate arrivals, including at least four mixed-bloods, who were recruited separately from the main body and arrived at Liverpool on board the Etruria on Saturday, 15th August 1891. So far as I have been able to determine, only Black Heart and Calls the Name, married in Manchester on 8th August 1891, were seconded from the Wild West to the White Lily party. There were therefore ten more Indians arriving in Glasgow towards the end of October 1891 than, relying upon Gallop, I had previously been disposed to imagine.

According to Gallop, The White Lily ran ‘between 24 September & 31 December 1891’22. He further records that it closed at Northampton’s Opera House on New Year’s Eve.23 It actually opened at the Theatre Royal, Hanley, on Monday, 31st August and closed in Northampton on Saturday, 2nd January 1892.

He refers to a telegram, addressed to ‘the manager of the Theatre Royal, Preston’24. F. W. Trevalion, the recipient, operating from 138, the Strand, was in fact Miss Clemmons’s manager-in-advance.

There is also the question of how many inhabitants of Preston turned out to greet the arrival of the White Lily Company at the railway station on the afternoon of Sunday, 11th October 1891, ‘to greet their arrival from London.’25 Unless Gallop is party to information which I have missed, it seems more natural to assume that the company had in fact come from the previous venue, Oldham - where the Colosseum theatre had been the venue on the previous evening. This lapse appears to be related to the error made in connection with Henry Irving’s departure from Bristol (supra) - once again, unwarranted assumptions have been made and Gallop has given London a greater part than it is actually entitled to.

Viola returned to London and prepared to spend the new year holidays alone. But she vowed to follow Bill across the Atlantic when he returned home after the close of the Glasgow season.26 If only Gallop had studied the passenger lists, he would have discovered that Viola actually went one better. When Buffalo Bill, having left the Wild West still running in Glasgow, sailed from Liverpool on Saturday, 30 January 1892, arriving at New York on Monday, 8 February, Viola accompanied him.

Gallop makes an interesting statement, concerning a ‘benefit performance to 6,000 local orphans’27 in Glasgow. The occasion was Christmas Eve 1891 but whether there were so many orphans in Glasgow at that time is open to serious question. In fact, Buffalo Bill’s young guests that day were children from seven of the Board Schools, as well as inmates of various Industrial Schools. The detail that they were orphans was a later embellishment of John M. Burke’s, surfacing in synopses of the show’s history appearing in the official programmes for subsequent seasons.

Outlining the latter phases of the 1891-92 Glasgow season, which drew to a close on 27th February 1892, Gallop intones:

Shortly afterwards, various members of the company returned to the United States. George Crager never again worked for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.28 In fact, Crager briefly returned for the 1892 London summer season. He sailed on board the Umbria from Liverpool on 30th July 1892, arriving at New York on 6th August. This was apparently his final departure from Buffalo Bill’s employ.

In the same context, Gallop issues a vague statement about the animals being put into winter quarters and unspecified performers finding work in British variety theatres during March and April 1892. I strongly suspect that he got this second-hand but wish that he had been able to provide more detailed information.

It is greatly to Gallop’s credit that he has got the story of the show’s development right, at least in broad outline, and is not amongst the many misdirected by Don Russell’s inaccurate dictum that the Rough Riders of the World were added during the spring of 1891. Nonetheless, his treatment of the subject is vague. He outlines the addition of ‘Cossack horsemen from the Russian Caucasus and a team of Gauchos from the Pampas grasslands of Argentina’29 to the programme for the 1892 London summer season. He might have added that these new arrivals were introduced in separate stages, the ‘Cossacks’ on Wednesday, 1st June, and the gauchos on Thursday, 23rd, but did not. Needless to say, he also fails to register the fact that the former were not Cossacks at all but ethnic Georgians. Mysteriously, he captions them as ‘Ukrainian Cossacks’30.

There were two further Lakota fatalities in London. The first was Long Wolf, whose grave in Brompton Cemetery was re-opened to admit a little girl named Star Ghost Dog. According to Gallop:

In the section of the show known as ‘Life Customs of the Indians’, depicting Indian life on the plains, White Star was placed in a saddle bag slung across the back of a horse and paraded around the arena with other small children from the camp. On 12 August, White Star fell from the saddlebag and landed on her head.31 His source for this is unknown. What can however be stated with certainty is that on the death certificate, dated 13th August 1892, Dr Coffin certified the cause of death as pneumonia, making no mention of any riding accident. The deceased’s name, incidentally, was given simply as ‘Star’ and she was designated ‘Daughter of Ghost Dog An Indian Brave’. Where Gallop got ‘White’ from remains a mystery.

At the end of the 1902-03 season, Gallop states that what remained of the touring company sailed on board the Lucania.32 In fact, the homeward voyage was undertaken on the Etruria, departing Liverpool on Saturday, 24th October 1903 and arriving at New York a week later, on the 31st.

A discrepency relating to Gallop’s account of the arrival of the first portion of the Wild West company is that he cites The Sphere33, listing the ‘Cossacks’ with the party arriving on the Lucania on the evening of Saturday, 16th April 1904; however, the Liverpool Daily Post34 indicates that they were part of the reception committee and therefore already present in England. This rather raises difficulties with the statement elsewhere on the same page that they had found professional engagements in the United States during the winter.

The following passage relates to the opening performance of the 1904 tour, on Monday, 25th April, at Stoke-on-Trent:

The civic leaders were also introduced to some of the Indians newly recruited into the company, including Young Sitting Bull – a son of the famous Chief – Charging Hawk, American Horse, Whirlwind Horse, Too (sic) Elk and Lone Bear, Chief of the Indian Police. The new recruits from Pine Ridge would also take part in the re-creation of the Battle of the Little Bighorn – Young Sitting Bull playing the part of his famous father and Johnnie Baker (wearing a long blond wig and built-up boots) in the role of General Custer.35 The information given concerning the Custer’s Last Stand sequence, if correct, is of course fascinating but this passage reveals another of Gallop’s key weaknesses; in this and in several other connections, the value of Buffalo Bill’s British Wild West as a work of reference would have been so much the greater if only its author had been willing to disclose his sources.

It might also be remarked that William Sitting Bull, otherwise Young Sitting Bull, was only available to acquit this role for the first few weeks of the tour, as he was one of the first to return home, suffering from health problems.

On 2-3 November 1904, the Highland Railway carried nearly 12,000 excursionists to the Wild West in Inverness – nearly 500 coming from the Orkney and Shetland Islands over 200 miles away. Huge numbers also visited from the Isle of Skye.36 This is a clear-cut instance of Gallop getting his dates mixed up once again. For ‘November’, read ‘September’. The fifty-one Indian performers still remaining at the season’s end disembarked from the Campania in New York City on 28th October and by 2nd-3rd November were presumably either well on their way back to Pine Ridge, or else had actually arrived.

Unaccountably, Buffalo Bill’s date of death is given as 12th January 1917.37 William F. Cody is conventionally reckoned to have died two days earlier, on the 10th.

One final complaint / concern / criticism / suggestion. In an appendix, Gallop provides a list of towns visited in 190338, in alphabetic order. He then repeats the exercise for 1904.39 Might not the dates have been provided and even the specific venues?

No one but Alan Gallop could have succeeded in compressing the entire story of Buffalo Bill’s British adventures into one single volume of manageable proportions and on this he is to be congratulated. However, in its present form, his magnum opus is marred by several clumsy mistakes and one is naturally led to wonder whether there is any prospect of a new and amended edition.

Footnotes:

1 pp. v-vi

2 Preface, p. vi

3 p. 19

4 p. 31

5 p. 40

6 pp. 55-56

7 p. 40

8 p. 133

9 p. 134

10 p. 267

11 p. 141

12 pp. 162 & 165

13 p. 164

14 p. 166

15 p. 169

16 p. 21

17 p. 20

18 p. 174

19 p. 177

20 pp. 179-83

21 p. 180

22 p. 181

23 p. 183

24 p. 182

25 Ibid.

26 p. 183

27 p. 185

28 p. 189

29 Ibid.

30 p. 192

31 p. 200

32 p. 236

33 23rd April 1904

34 18th April 1904

35 p. 237. It might incidentally be observed that Gallop once again contradicts himself at p. 268, by giving the date of the opening performance, erroneously, as ‘April 24’.

36 p. 240

37 p. 252

38 p. 268

39 p. 269